Patrick Nagatani

Nagatani / Tracey Polaroid Collaborations (1983-89)

The collaboration began in 1983 when Nagatani was offered 2 days use of a 20” x 24” Polaroid camera. He was a photographer, Andrée Tracey was painter and they occupied studios in the same Los Angeles building. Tracey’s sensibilities coalesced with Nagatani’s ideas and set design experience, and with this alliance, their collaboration was launched. Using aspects of photography, painting, installation, and performance. Working in a theatrical way they expanded the boundaries of large format Polaroid 20X24 photography. The recurring theme through much of this work is the threat, the chaos, and the consequences surrounding a nuclear episode. Both artists appear as actors in elaborately constructed and intensely colored images which are peppered with irony and humor despite the darkness that the work forecasts.

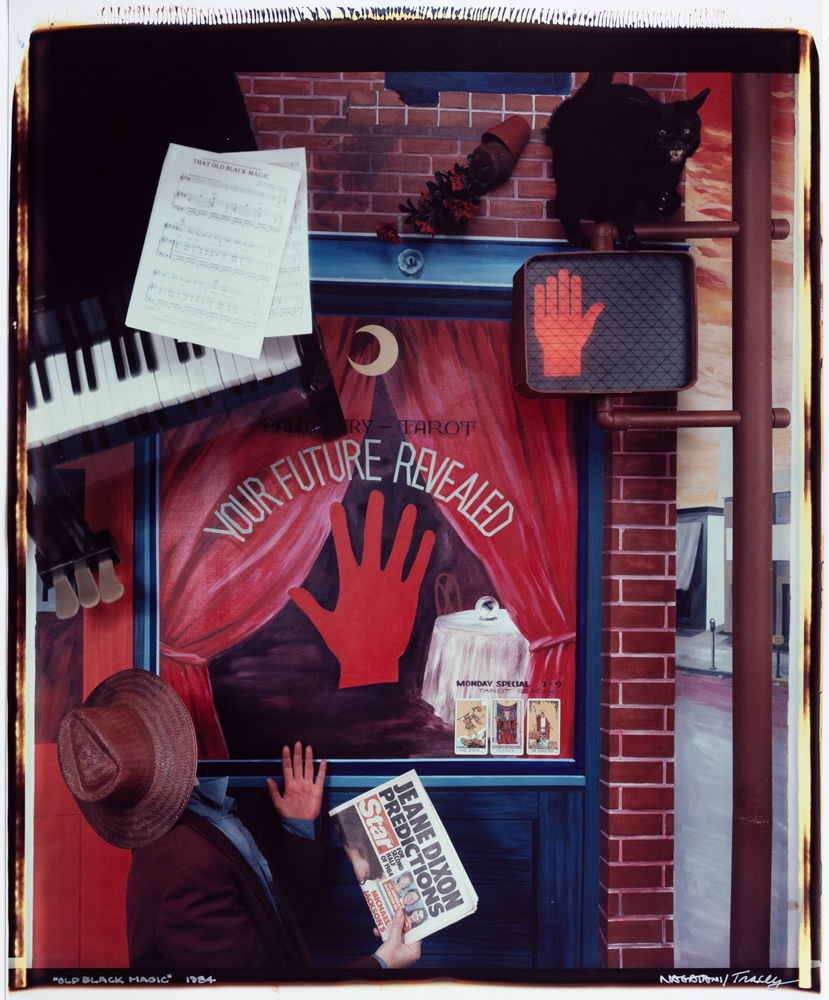

Old Black Magic, polaroid print, 1984

Barbara Hitchcock - Polaroid and the Nagatani/Tracey Collaboration

It’s an atomic explosion! Red-scorched palm trees, pizza, pills and milk cartons soar through the air with glass shards, shattered eggs, beer bottles and bags. An inspired, if somewhat foolish, photographer records the apocalyptic catastrophe, his SX-70 instant photographs sucked into the violent maelstrom cascade over his head as they spit out of the camera. One photo captures the ghastly mushroom cloud juxtaposed against a deserted, scarlet landscape. The other photographs reveal nothing but red—incinerated earth? ash-filled atmosphere? Perhaps these tiny prints foreshadow the beginning of a new world. Life as we know it can change in an instant.

Hung pinned to a wall, sheets of 20x24-inch Polaroid film―two dimensional versions of the adjacent three-dimensional set―document the apparent destruction. A forest of objects dangle from lines of monofilament precisely located in front of a painted canvas backdrop that features office buildings and a modest skyscraper, tinged red by the blast. The crazed photographer’s jacket, tie and hair are wind whipped by the concussive force. Or so it seems. There is more artifice than meets the eye. The canvas cityscape rests on its side while Patrick Nagatani, portraying the unlucky shutterbug recording the moment, enters the photograph. Beyond the camera’s view, half of his body lies stretched on a table. His upper body thrusts unsupported into the picture frame. The illusion is complete. The shutter clicks. Red Piece is born on film. The story is told.

Red Piece study, polaroid print, 1983

Impending nuclear calamity captures the imagination of artists Patrick Nagatani and Andrée Tracey, the co-conspirators who spent six years creating dooms-day scenarios. Natural disasters, obesity, and similar themes are in their sights, but the primary target of their creative energy is the threat of nuclear annihilation. They began to collaborate in the ‘80s, taking a critical, yet fanciful look at society, politics and the environment. In their eyes, man’s situation in today’s world is notably precarious. Fabricating stage-like sets that they then photograph, the artists parlay fact against fiction, seeking to grab your attention, compelling you to stop, look and think about the messages communicated in their photographs. “We think of our work in terms of sociological or political comments,” Tracey says, “but with a sense of humor.”

The artists met when they both taught at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Their studios were in the same building. Patrick made photographs, used mixed media, always tried to stretch photographic conventions. “There’s a certain edge to photography that’s really restricting,” he says. “It’s a controlled medium, especially in the process. And I just want to throw that control out as much as possible.” Once a graduate student of Robert Heinecken’s at UCLA, Nagatani’s resistance to the constraints of traditional photographic practice is in keeping with his training. Time spent in Hollywood building models and sets for movies, among them Blade Runner and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, also influenced his desire to push boundaries. He envisioned a more expansive, plastic kind of photography.

A painter, Andrée invented bright, vibrant, humorous images, rendering them in paint, and sculpture―perfect compliments to Patrick’s photographs. Also a photographer and sculptor, she had made storyboards for television and films. Their experiences meshed perfectly, setting the stage for creative thinking and execution. Taking an idea, they’d flesh it out with detailed drawings, designing the look and feel, collecting props, painting backdrops, figures and objects. With all the components gathered, constructing a set began. From start to finish, they were the producers, the directors and the actors who frequently appeared in front of the camera. The entire process could take weeks, if not months. Then the camera records the installation in a moment.

Nagatani and Tracey first encountered the Polaroid camera when they were invited in 1983 to participate in a photographic project held at the Museum of Photographic Arts in San Diego. Six prominent West Coast artists would photograph in a specially constructed studio adjacent to a gallery where The Big Picture, one of the first Polaroid exhibitions comprised exclusively of 20x24 photographs, was displayed. Museum goers could see the exhibition and simultaneously observe artists making more photographs to hang on the walls. It was photography, installation and performance art all rolled into one experience. With their limitless energy and shared black sense of humor, the duo was particularly entertaining.

Pulling large photographs from the base of the camera, they combine them end to end, making diptychs and triptychs... The color was dazzling; the detail, extraordinarily sharp. Painted brush strokes and suspended monofilament are easily detected in the chaos of objects and the occasional human that populates this world. “The 20x24 camera was the perfect vehicle for combining our talents,” said Tracey. “We worked in a complementary and elastic way with things never completely hammered down. Beyond the planning and constant interchange, our ideas took on a life of their own by the final shoot.” For any audience, it was quite a show.

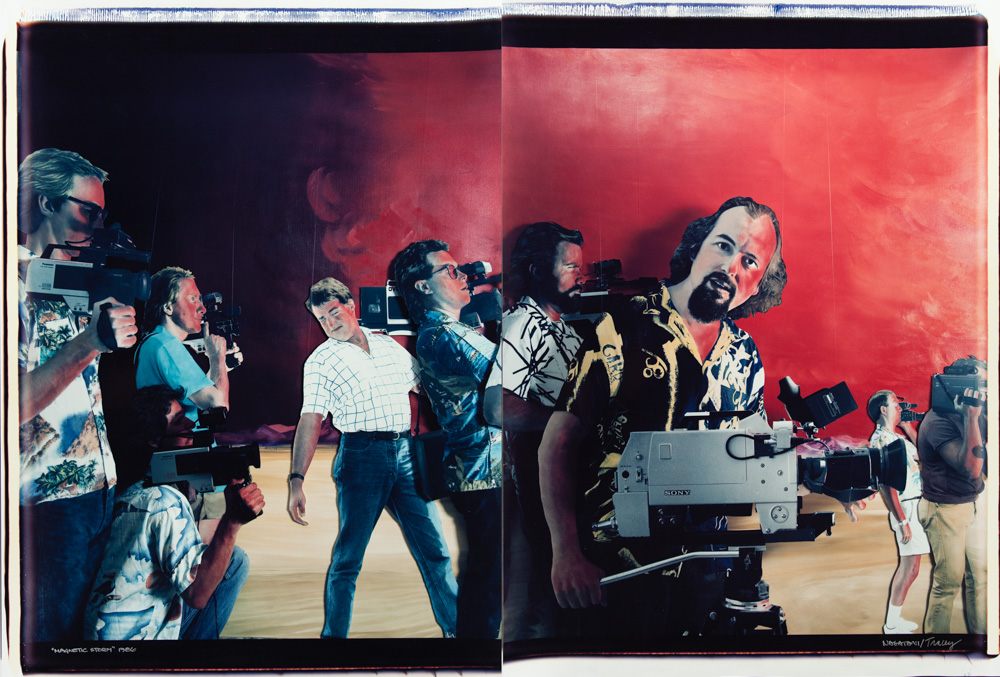

Magnetic Storm, polaroid prints, 1986

Nagatani uses color purposefully as he believes its use can stimulate different psychological reactions in onlookers, from those that are quiet, calming and meditative to those that are emotionally charged. The brilliantly saturated or muted reds coating every object in Red Piece trigger visual dissonance and angst. In Atomic Café, Tracey painted two men sitting back to back in different booths inside a local L.A. eatery. The men, bathed in dark blue hues, ignore one another while behind them, framed in a red-curtained window, cars flash by disobeying speed limits. The hustle and bustle of city life is in full force as an ominous cloud of dust obscures the sky and treetops. Tracey herself steps into the scene completely dusted in vermilion, wearing a red dress and apron, just as her tray of wine glasses and a bottle of merlot begin to tumble. Sandwiches, fries, noodles, plates and cutlery lift off the tablecloth as some mysterious force pushes them airborne. In the midst of all this action, the blue men remain still and unperturbed. But we know danger looms.

“The black humor in their work,” writes photographer and critic Mark Johnstone, “has relations to various disparate sources, such as: large set advertising photography, “Pop” painting of the 1960s and the political sarcasm of editorial cartoons. Social disasters of various kinds—from the evolving complexities of urban life, to the raw and wonderful horror of nuclear bomb blasts—are magnified and emblazoned in stunning colors.”

Similar to their other atomic photographs, 34th and Chambers is a dazzling red creation, only slightly muted by the metallic blue-gray of a subway train that’s just stopped to pick up passengers. A crush of commuters struggle to get on or off the train, just as a shock wave tosses spray cans, calculators, candy bars and coffee cups toward the ceiling. Some passengers are pushed off balance by the wind. Others look quizzically over their shoulders. A sense of alarm, distress, uncertainly is palpable. Yet, a handful of commuters are lost in thought, blissfully unaware of their environment.

The subway station is inhabited by painted faces, life-sized photographic cutouts of family, friends, artists and their pets. Nagatani and Tracey, along with the flying detritus, are the only reality in this tableau vivant. Fact and fiction intertwine once more. What was another imaginative interpretation of nuclear holocaust when the photographs were made in a Manhattan studio in 1987 now seems prescient. Even the most unimaginable chaos can happen in a political landscape over which we have little, if any, control.

Nagatani and Tracey bend the truth with an ironic twist in their reconstruction of an atmospheric nuclear weapons test—Operation Greenhouse-- conducted in 1951 by a joint U.S. military-civilian organization. Observers of the test sit expectantly on rocks and lawn chairs awaiting the detonation over the Enewetok Atoll. Over-sized dark goggles obscure their eyes as the first searing wave of light hits them. Similarly, in Alamogordo Blues, stereotypically attired, blue-toned Japanese businessmen wearing protective goggles sit in Adirondack chairs shooting the nuclear inferno with their SX-70 cameras. Red prints sail over their heads as they develop, displaying a notorious mushroom cloud in a fire-red sky. The Alamogordo Bombing Range in the New Mexico desert hosts this extraordinary scene, its Saguaro-dotted sands stretching to a distant mountain range, tinted mauve by the blazing light. It is difficult to miss the irony in this multi-layered image. Disguised in dark humor, it is a lament and theater of the absurd played out in graphic detail. “The ability to dream and think of the issues [brought up by the work] is more important than truth,” Nagatani says.

The Nagatani-Tracey collaboration signified a short, but intense span of creative energy. Their photographic narratives present critical viewpoints with humor, biting wit, scintillating color, histrionics and a sense of fun that are highly seductive. We pay attention. We smile. We get it. Their message, with its serious undercurrent, surfaces.

Alamagordo Blues Variant, Cibachrome print, 1986

Nagatani was a pioneer in the 1980s in reviving the movement of narrative tableaux (tableau) photography, a tradition in photography since its inception in which photographs are staged, posed and manipulated. Beginning in the 1840s with British Victorian pioneer photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson who posed scenes written by Sir Walter Scott with friends dressed as monks, knights and bards. This storytelling continued into the late 1850s when Oscar Gustave Rejlander began producing composite narratives and Henry Peach Robinson made images consisting of multiple negatives and double exposures. Julia Margaret Cameron posed her famous subjects in allegories, religious and literary images, and narratives. Among 20th century photographers F. Holland Day, Gertrude Kasebier, and William Mortenson created images involving medieval passion plays and religious, moral, and social issues. In these the photographer become the director and in much of Nagatani’s work he is also the director.

There are countless examples by amateur, professional and artistic photographers, but generally the major photography movements of the early and mid 20th century were inclined toward the ideas of fidelity and truthfulness in what the camera sees and how the photograph is made The F-64 school of Edward Weston and Ansel Adams, the decisive moment of Henri Cartier-Bresson and the journalistic and documentary styles of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank, the zone system, and emotive photography, all involved using single negatives as they were created. Central to this is the idea that what the camera sees is truthful and consequently the output, the photographic print is the ultimate representation of that truth.

For an informative history and discussion of narrative tableau in the History of Photography and how that led to work by Patrick Nagatani and Gregory Crewdson see: PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRESENTATIONS OF 'TRUTH': THE HISTORY AND CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC NARRATIVE TABLEAUX by D’Arcy L.J White a Masters Thesis Ryerson University, Toronto, George Eastman International Museum, Rochester, 2010.

https://digital.library.ryerson.ca/islandora/object/RULA%3A6724

Atomic Ayers (triptych), 1989

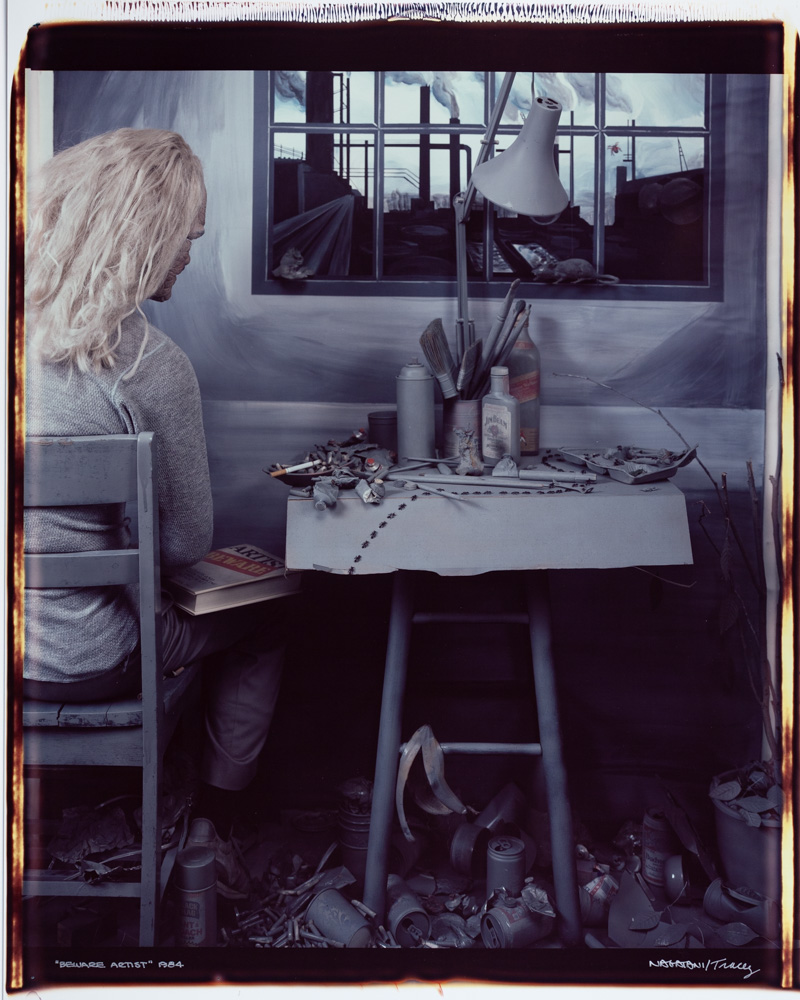

Beware Artist, 1984

Blue Room, 1986

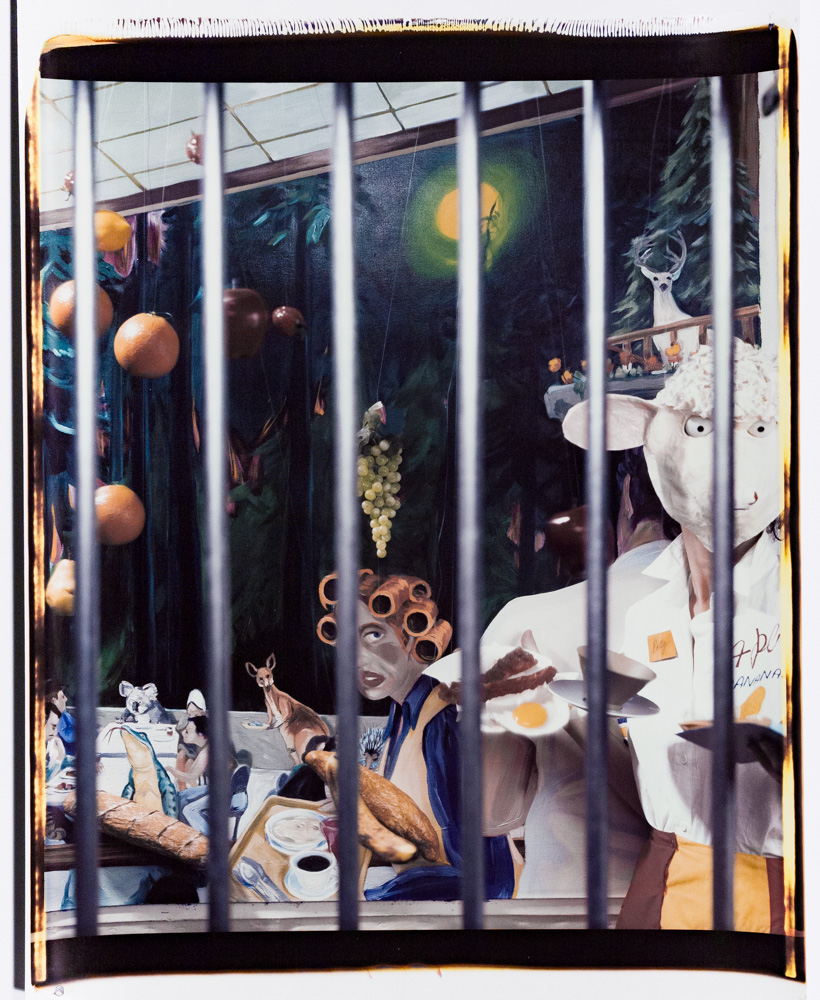

Cliftons (Unreleased Series), ca. 1986

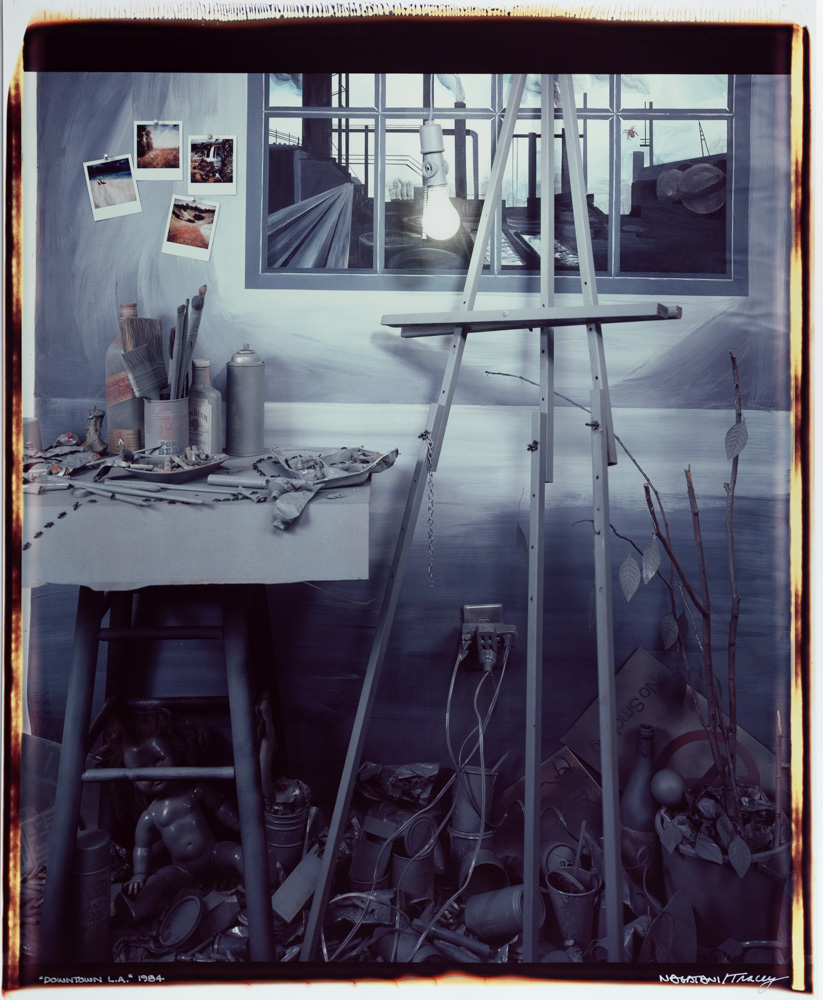

Downtown L.A., 1984

Missile Mentality, 1988

Radioactive Inactives, Cleveland, Ohio, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, Detroit, Michigan, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, Los Angeles, California, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, Lubbock, Texas #2, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, San Francisco, California, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, Sioux City, Iowa, 1987-1988

Radioactive Inactives, St. Louis, Missouri, 1987-1988

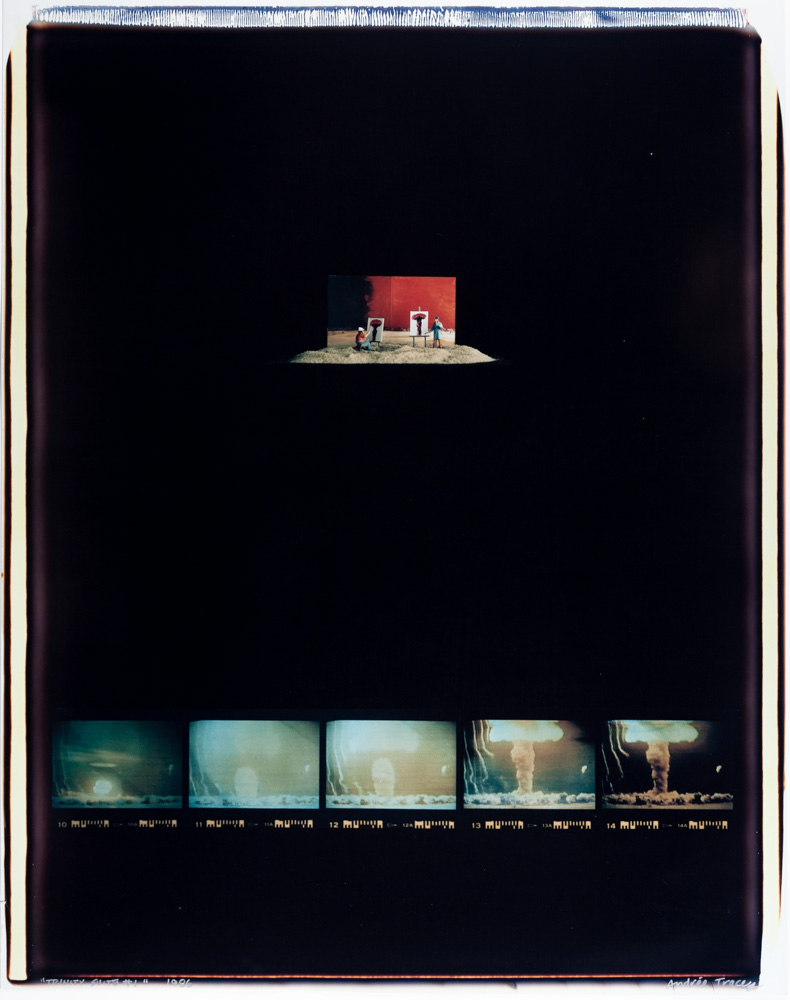

Trinity Suite: Untitled #1 Of 7 (Painters), 1986

Trinity Suite: Untitled #2 of 7 (Bride & Groom), 1986

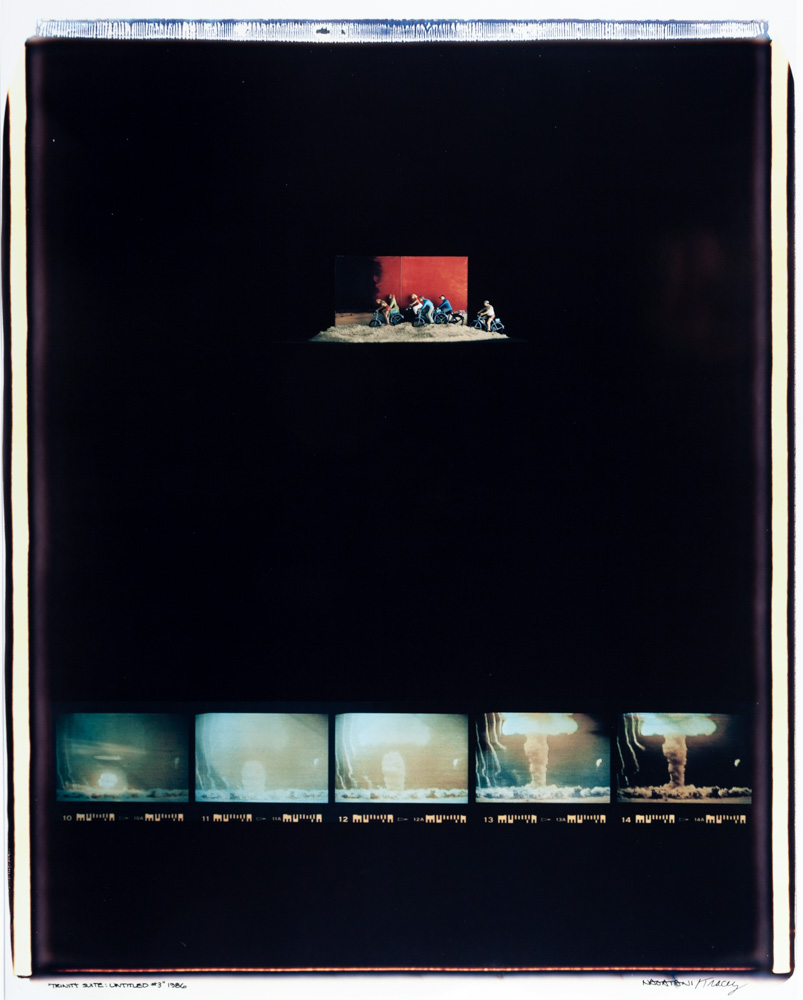

Trinity Suite: Untitled #3 of 7 (Bicyclers), 1986

Trinity Suite: Untitled #4 of 7 (Photographers), 1986

Trinity Suite: Untitled #5 of 7 (Bathers), 1986

Trinity Suite: Untitled #6 of 7 (Luggage), 1986

Trinity Suite: Untitled #7 of 7 (Elephant), 1986

Was It Heinecken Or Lyons, 1984