GEORGE W. GARDNER

Gun People 1984

with text by Patrick Carr

The Andrew Smith Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition,

George Gardner: Gun People. There will be an opening reception on April 9th, 2022, from 7pm - 10pm. The exhibition will continue through May 15, 2022.

"America is my place.... I have no choice, and I have always felt that. Anyplace else, I’m just a tourist, I don’t connect. In America, I feel as if I have some deep notion of what’s going on. I am trying to get at what I think about America. I can feel this country." - George Gardner

Exclusively represented by The Andrew Smith Gallery, Tucson, AZ., Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, and Paul M. Hertzmann Inc., San Francisco the collection of American documentary photographer George W. Gardner (b. 1940) comprises thousands of photographs realized largely between 1960 and 1988. His far-reaching work, truly an "American document," reveals his deep empathy for the American experience, from the most ordinary moments of daily life to events that have shaped American history.

Whether practicing primarily as an independent photographer and choosing his own subjects or working on assignment, Gardner created a unified vision that defines and encompasses the American experience.

In 1984 journalist Patrick Carr and George W. Gardner published Gun People. In interviews and environmental portraits of Americans who used guns, this prescient landmark explores one of the most controversial arenas of current political, personal and journalistic interest. With nuance and complexity, the book delves into the large and small issues around all aspects of this debate.

The Gardner portraits combined with the first person interviews create a highly charged document which now stands as the most important documentary study of a large segment of the American population in the late 20th Century. It is unflinchingly straightforward in its photography and texts, examining guns, history, paranoia, fear, machismo, hubris and common sense.

Gardner did not approach his subjects for this project as an outsider. Both a photographer and animal trapper, he grew up in rural America where there was little controversy over the practical aspects of gun ownership. The results are consummate photographs devoid of confrontational irony or judgement.

In the introduction Carr summarizes the statistics (at that time) and positions in the pro-gun and gun control debate:

The United States is the only nation in the world which specifically grants its citizens the right to own and bear arms. The Second Amendment to the Constitution declares that 'A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.'…

In the latter half of the twentieth century, the American’s right to self-protection with a gun has become a central issue in both the nation's perception of itself and the eyes of the world, and ever since the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the overall trend has been toward tighter control (or elimination) of the private citizen's legal access to firearms. Behind this trend is the notion that large numbers of guns in the hands of the citizenry encourage crime and deadly violence that would not occur without the availability of such instruments.

Recently, however, that notion has come under concerted attack, and is no longer the article of political faith it once was. The sweeping trend toward tough gun-control laws is now a hard-fought, bitter, and often unsuccessful campaign. The notion that we live in a society which is far from 'civilized' and should act accordingly has risen to the fore, and more and more Americans of all political stripes are showing deep interest in the techniques of self-preservation…

The furor surrounding the debate is, in a way, responsible for the making of this book. The debate is so hot, and its issues so central, that it tends to be the only gun-related matter to which journalistic media professionals are willing to apportion time--which means that it is the only nonfictional gun--related information received by media consumers. Fictional input, of course, is available in megadoses--how would prime-time television sound without all those lively ripples of submachine gun fire, those manly shotgun blasts, the casual popping of .38s and '45s and '22s which keeps every plot line…moving right along?...

Obviously, there is a disturbing schizophrenia here, a strange and irrational divergence between the media's almost universally anti-gun journalistic coverage and its wholehearted fictional commitment to the gun as the power and glamour object, and the resultant middle-ground reality gap is communicated to media consumers….

It was this characteristic of media output, and the strength of the media-generated stereotypes available to me and those around me, that initiated my decision to embark upon Gun People; basically, I was curious, I wanted to find out who the 'gun people,' really were.

...Gun People demanded the 'oral history' approach. The whole rationale behind the book stemmed from the fact that the voices of 'gun people,' if heard at all in the mass media, are routinely muffled by the louder voices of the editors, producers, and reporters presenting them, so the task facing George Gardner and myself would be to simply present those voices as clearly as possible, regardless of our personal opinions of what was being said, The copy in the book, therefore, should be in the form of first-person monologues edited from tape-recorded interviews. Gun People is

not about gun people; It is gun people.

It is difficult to step back from the gun control debate, but I believe that some essential points about it must be made, and I feel compelled to make them. My position is that of the man in the middle; ever since beginning work on Gun People, I have been exposed to the arguments of both sides on a daily basis, and have become uniquely familiar with their ins and outs, and also their broader characteristics.

Given that, it seems to me that overall, the statistics favor the pro-gun forces, but those forces offer us a social scenario which is deeply disturbing. While their wish to see recreational shooters and responsible hunters take their pleasures without undue restriction is morally unassailable (except by animal-rights activists), the implications of their stance on handguns for personal protection are grim indeed: their relentless fight to guarantee the American citizen's right to defend his or her life with a gun implies that such an extreme is necessary in our society. That is a hard notion to sell to a nation which prides itself on its compassion. So, for the same reason, is their argument that what this country needs is not more restrictive gun control legislation, but a criminal justice system capable of removing the threat posed by violent criminals. Their basic point that a national handgun ban would be nothing more than a placebo for the liberal sensibility--is a very bitter pill indeed.

The gun-control advocates, on the other hand, seem to offer little in the way of persuasive statistics, but the basic emotional appeal of their cause-Guns kill people! Get rid of the gunsl Stop the killing!-is enormously seductive. One horrific incident of public mayhem like the 'McDonald's Massacre' of 1984 is fully capable of winning literally millions of supporters to their cause despite the fact that it obscures the less newsworthy but no less brutal (and infinitely more frequent) daily violation …[by stabbing and beating]...of unprotected citizens in their homes…

The arguments, therefore, are very different in tone and implication, and it is the great irony of the debate … that neither argument—one grimly pragmatic, the other heartbreakingly optimistic--can have any effect on the basic philosophy of its opponent.

Now it is time to meet some gun people.

"I started doing less shooting in high school."

Andrea Coulehan, an artist and mother who lives in Lenox, Massachusetts, shot a gun for the first time in fifteen years on the day she was interviewed.

I began shooting at the age of about ten because the late Al Dynan took me under his wing. He was a top shooter in the Northeast and he was also like a father to me.

We'd go out in the back and shoot his .45 whenever I was over at his house, which was frequently, and I really loved it. A gun is a very powerful thing, and as a kid, being able to shoot a gun was a big thing. None of my friends shot guns; they didn't do anything like that. I made bullets and everything, and I felt really good about that at that age.

I didn't really talk about it at school; it was just something special to me. And I was always outside, I was always sort of the tomboy of the family, so it was really natural for me to hook up with someone like Al, who didn't have any kids. He really liked showing me things, taught me how to drive his Jeep and stuff. He had hunting dogs, and I loved that whole life, I just thought it was wonderful. He was a country boy, very civic-minded, very bright, very compassionate. He had his own gun shop there in the house, and he had business from all over the country. Artie Shaw would come to the house, people like that. He made guns, too, and he was a hunter, and he would take me out hunting. He was a real sportsman, you know. He was a man’s man. It was all very powerful, I thought back then. I still do. That type of man is always attractive to me.

At Al's funeral there were a few younger people who expressed the same kind of feeling for him that I have, so I think he had other kids he took under his wing. I never knew about anybody else at the time, though---l thought I was his little girl. I think I was, really. I really miss him now that he's gone. I really miss him. Still.

I started doing less shooting in high school, with boyfriends and activities and so on, and then I went away to college, and then I got married, and that kind of ended it. I just didn't see Al that much after that. But back when I used to go over to his house, he would really make sure that every time we would go out to the range in back and shoot. He really thought I had a lot of potential.

I never knew about this till later, but he talked to my parents about getting me into competition. They didn't want me to do it, though. I don't know why. I mean they would let me go out on the range in back and shoot, so it wasn't as if they thought I was going to have a bad accident or something. It really doesn't make any sense. I wish that they'd let me. I just really don't understand why they did that. Pistol shooting at a target is just a great sport, and I really loved it. I was good at it, too.

When I shot just now, it felt great. It still feels great. I really started shaking after I shot those two shots because I haven't fired a gun in so many years, but I was still good!

"I average about three hundred per season when their fur is prime."

Ray Milligan, pictured with his three children and his Savage over-under 22/20-gauge combination gun is a professional fur trapper based in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

During the late sixties and early seventies, the Vietnam years, mv wife and I were part of the back-to-nature movement. We bought a small farmstead in north-central Kansas and had our three children there. My wife did pottery and weaving and stuff, and we had milk cows and pigs and chickens and ducks and goats, and I was a predator trapper. Then I wrote a book or two on trapping, and started to manufacture scent lures to attract wild animals. That business got going very well, establishing us nationally, and that afforded us the luxury to live anywhere in the country. We picked the Santa Fe area because it's a cultural hub, and because it's a very good area for trapping coyotes.

I chose coyotes because they are very destructive to livestock--their natural niche in this world is as scavengers, but when times are tough they become wolf-like and kill sheep and even cattle-so landowners open their gates to me. Usually, access to land is the trapper’s biggest problem.

Coyotes, in fact, have become quite a pest in recent years. Historically, they were a Plains animal, scavenging after the wolf packs which followed the buffalo, but something happened to them following the poisoning campaigns which ended in 1972. They dispersed, and now you find them everywhere. It's a phenomenon: nobody really knows why it happened but we do know that coyotes are highly intelligent animals. We judge the intelligence of animals by the number of vocal sounds they make, and studies have shown that excluding primates, the wolf makes the most vocal sounds of any mammal. The coyote makes one sound less than the wolf, tying with the dolphin.

That makes them the hardest furbearers to put into a trap, but I do pretty well, I average about three hundred per season, when their fur is prime and they qualify as a renewable resource. They really are renewable, too. A female coyote is a very efficient and adaptable reproductive machine. If I go into a particular area and eliminate 60 percent of the coyote population, the females will react accordingly that year and produce large litters. If I hadn’t gone in there, there would be less food per coyote and greater stress, and the females would react by producing smaller litters. I go back to the same farms every year, and every year I take eight or ten coyotes there.

I have no trouble selling the fur; the American fur market is growing these days because average Americans are beginning to realize that like the Europeans, they might never be able to afford their own house, but they can afford a nice car and they can afford a nice fur,

I take the Savage with me on the trap line. The .22 barrel will dispatch animals in the traps, and the 20-gauge shotgun barrel is for when they bust out of the traps, which they often do when you get near them. It's a simple gun without a lot of technology to go wrong, and I can depend on it. When it's twenty degrees below zero, or when I’ve dropped it in a river going after a raccoon, it will work.

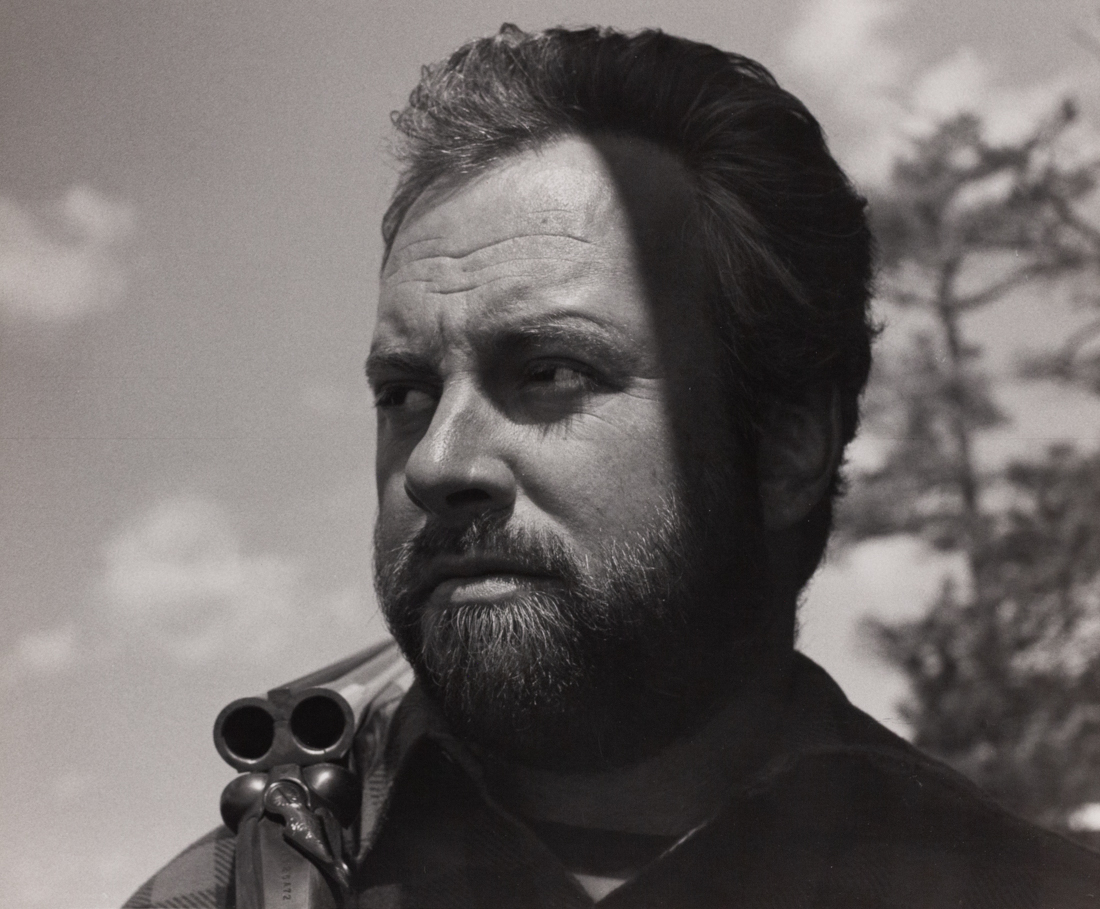

"An inexperienced person with a gun in hand is more dangerous than a bear."

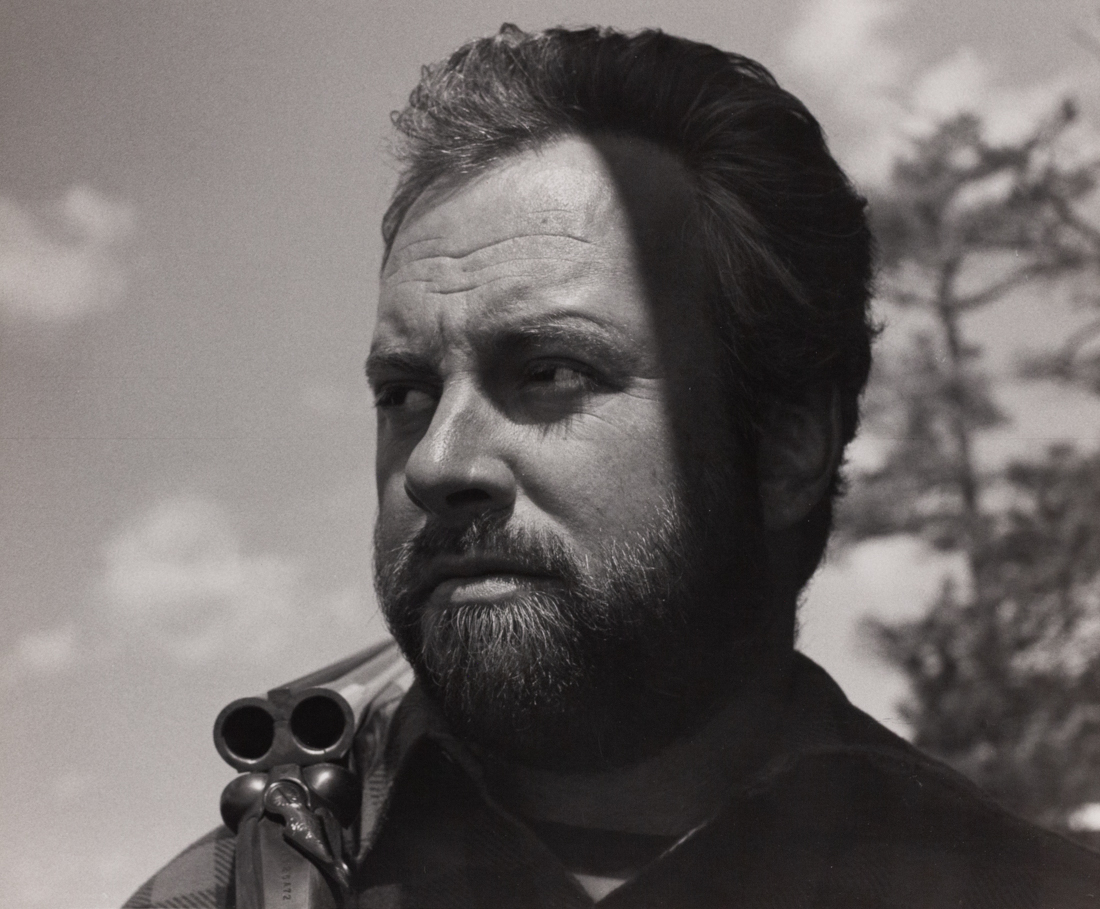

Ron McMillan (with shotgun) runs the Bristol Bay Fishing Lodge in the Wood River lakes system of Southwestern Alaska.

Up here we hunt anything from caribou and moose to ducks and geese, and of course there's bear. We've got quite a few Alaskan brown bears right around here. Some people call them "grizzlies," but any bear that's more than seventy-five miles from salt water is classified as "a grizzly," so you can call it what you want.

You have to watch out for them. Once in a while we'll get one come into the camp. Last fall, one came right up on the porch, and my wife had her nose against the window glass, looking out. The bear put his nose right up against hers, looking in. In the fall, I pretty much don't set foot outside the house without a gun, especially when I go out to turn off the generator for the night. It's pitch black out there, and you can run right into each other. People around here always have a gun handy.

This place here we call "Bear City." It's a place that people normally can't or don't get into, and there's a lot of salmon running in the river and lot of good berry bushes along there, so it's a good food source for the bears. There's high grass in there, and they'll lay up in it during the daytime. We fish there, and since I just don't want to walk up on one, before we go in I'll crank off a couple of shots to let them know we're coming. Usually they'll get up and look around, or they'll get up and run. These are very, very wild bears. They're not like the ones you run into in the lower forty-eight; these bears don't know people, so if they hear you talking, they'll leave.

I use a Ruger bolt-action .338 Magnum when I'm bear hunting, and I load it with 250-grain silvertips. For protection when we're fishing I use a l2-gauge pump or a .44 Magnum sidearm. I load the pump with Magnum slugs backed up by double-ought buckshot.

With the .44, let's put it this way: it's the most powerful handgun you can carry, with the muzzle velocity being what it is, so if a person had time to get it out, I think it could do a bear in pretty well at close range. I hope I never have to use it, though. I’d much rather use the shotgun. Still, it's a pretty mean handgun, and most people around here put a lot of faith in it being able to stop a bear at close range. Most of us who are carrying handguns are carrying a .44. The longer the barrel, the better. When you're carrying a lot of gear, sometimes you can't carry a shotgun too, so you have to rely on that .44.

We encourage our fishing clients not to bring any guns with them, because so many of them have the story in mind that every time they see a bear, they're going to have to use that gun. That's not true, and an untrained, inexperienced person with a gun in hand is more dangerous than a bear.

"A bird would come up, and subconsciously, I’d shoot to miss"

Sandra Cipollino, a New York State medical secretory began shooting seriously three years ago, she competes in trap and skeet matches and hunts pheasant and deer.

My first deer hunt was a strange experience. My husband had just gotten a .357/.38 combination Rossi lever-action carbine, which is a nice, light woman’s gun in the woods, and we went out into the woods with it. I was standing there, and I saw this doe. We had a doe permit, so I put the gun up, but I got so nervous I said, I can’ do this!”

I put the gun down, and my husband said, “You dummy! What are you doing in the woods with a hunting license and a gun if you're not going to shoot it?

So I picked the gun up, and I shot, and I got my first deer. Then it was like, I don’t believe I got it! I didn’t have any bad feelings then--it all went through my head before I shot. Once you've pulled the trigger, it's over. You either get it or you miss it, and that’s what’s, important. That first time, it was so funny—I tell you, I never shook so hard in my whole life, about anything. The adrenaline rush is really something.

I guess I wasn't really sure about whether or not I was going to do it when I went out; it was the whole idea of shooting an animal, how to justify that to myself. It was like when I first started pheasant hunting. I’d be walking along and a bird would come up, and subconsciously I’d shoot to miss. But I just had to make a resolve--either I started doing it, or my husband wouldn’t take me hunting anymore--and understand that I was shooting them for food, that they weren’t just going to waste. That’s how I justify it, and how I can enjoy it. And when you shoot your first one, and watch your own dog bring it back to you, it’s really thrilling to see it all happen together. I can’t really explain it, but it's so exciting, all of it. And I’m getting pretty good. If I get a chance to shoot at a bird, I don’t miss.

I guess I'm the best woman shooter right around here and in a lot of the trap and skeet matches we shoot, I’m the only woman. I've tried to get the wives of some of the men shooters into it, but they don’t seem as interested as I am. It's like with women in general-l get some strong reactions when I tell them that I shoot. They find it totally amazing. They'll say, "You shoot?” Then they’ll say “Oh I've always wanted to try it,” and you say, “Well, try it! Come out and shoot!" But they don’t. I guess they just don't think women should shoot. It’s like a friend of ours who started shooting recently: his wife is so terrified by guns that when he built their house, he had to build gun closet with a secret panel. She didn’t even want to know what room the guns were in!

You get some men who are weird about women shooters too. I applied for membership in a club around here, for instance, and it was approved by all but three of the men who had to sign it. I found out who they were, and went and talked to them. It turned out that they didn’t want me in because they couldn't be “men” if I was there. They didn't feel that they could swear, and if they wanted to go to the bathroom outside they couldn’t do that--you know just be "men." What can I say? They all signed.

"The United States is a great training ground for terrorists."

Ray Haas is a counter-sniper and training officer with the Hillsborough County, Florida, Sheriff’s Department Emergency Response Team. He is pictured with his ERT weapons.

My ERT guns are a customized Colt 45 Government Model pistol, a lightweight M-15 assault rifle, a Remington 1100 l2-gauge shotgun modified for combat use, and a Remington 700 sniper's rifle in .306.

The .45 is our personal weapon, and it's also the only gun we use in entry situations. A handgun allows you good reaction time and target selectivity, it's easy to reload, and the .45 round won't go through walls and hit your own people or civilians. Also, it doesn't have a long barrel; with a long barreled gun, you run the risk of letting the bad guys know where you are, or having them grab the barrel as you go through a doorway. That's why our entry teams don't use shotguns; our shotguns are for firing gas shells and blowing the hinges off doors, that kind of thing.

We use the .45 because of the knock-down power of the .45 round. Once modified, the gun will put two very quick hits on the target, and will function perfectly 99.9 percent of the time; just like Ivory Snow, it's 99 9 percent pure.

My designation is "counter-sniper," and that's why I have the Remington 700. It does the job. It has a Brown's fiberglass stock, one of the first they made, and that keeps it at constant zero; I can put this gun away for a month and it will shoot exactly where it always did when l take it out again With this gun, I can make head shots at six hundred yards, and five out of eight body kill shots at one thousand yards. I put quite a lot of my own money into like I do with most of my equipment, but I'm with people's lives here, and I have to trust my equipment.

Contrary to the public image of SWAT teams, we don’t use the M-16s that much. The .223 round has very high penetration, so we won't use the M-16s in entry situation or in densely populated areas. They are for perimeter use for assaulting buildings without entering them, and, should it ever come to it, for laying down a barrage of covering fire.

We've never had to do that in Hillsborough County. We've had to deal with disturbed people and bank robbers who were armed and holed up somewhere--in one case with explosives rigged--but we've never had a serious, professional problem with an organized group, hard-core terrorists. The closest thing to that in the United States is the biker groups. They're well armed and they train, and they could be effective.

Personally, I don't foresee too many immediate terrorist problems.The United States is a great training ground for terrorists-it's the only place where they can move freely, buy weapons, train with weapons, do whatever they want to do-and they don't want to ruin that situation by performing terrorist actions here.

That makes it easy for the people who don't want police departments to spend a lot of money on guys like us. They'll change their tune if a real problem does arise, of course, and then we’ll all be playing catch-up with the terrorists.

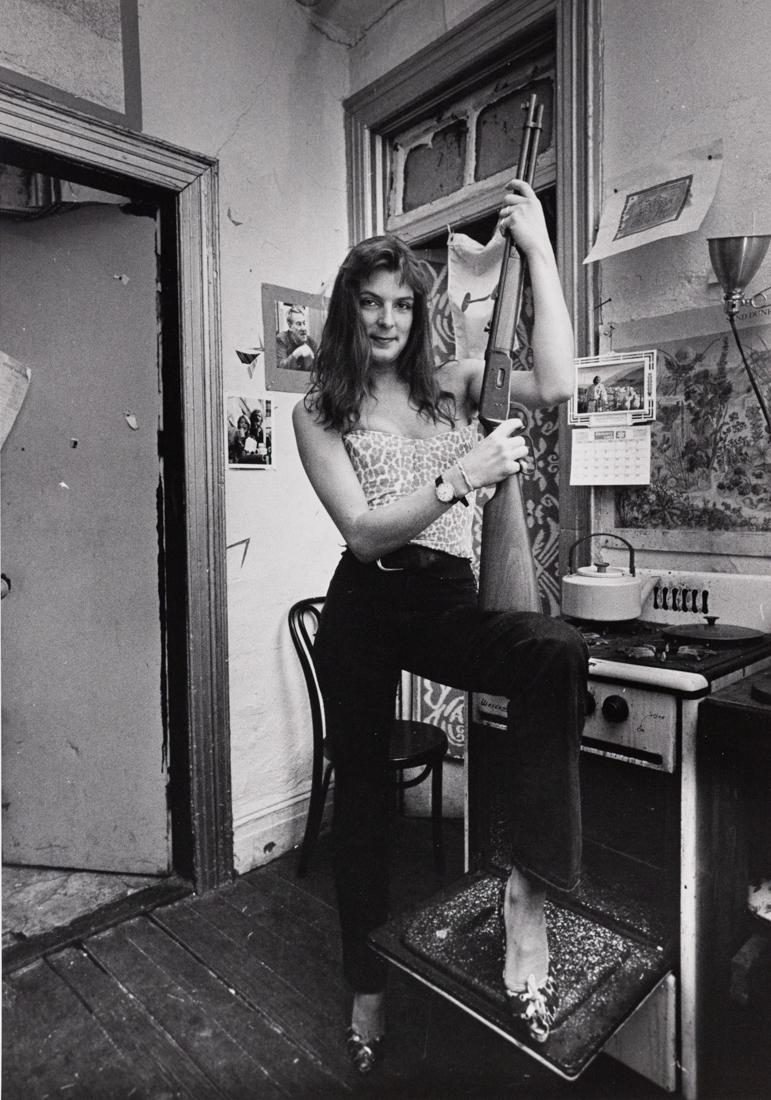

"I think it's legal for me to have it, but it damn well ought to be illegal."

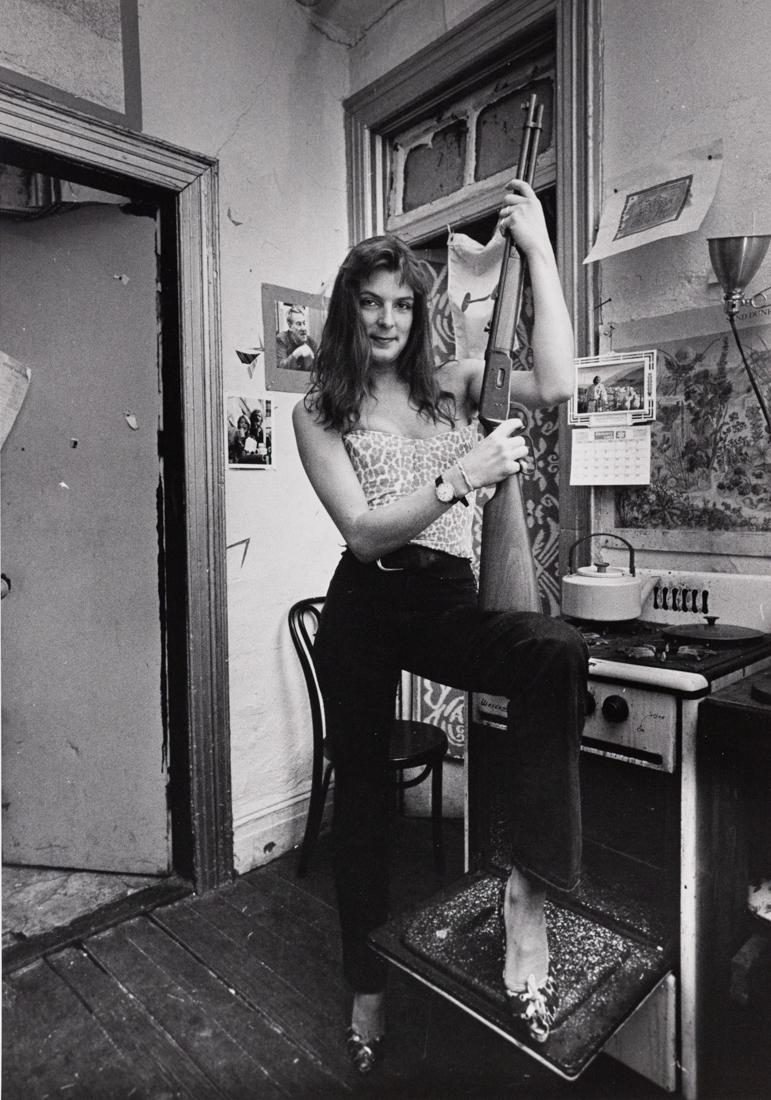

Patience Pierce lives on New York City’s Lower East Side. She owns only one gun, a Winchester .30-30 rifle.

My ex-husband gave me this gun in New Orleans. It was on my first date with him, he gave me the gun, and he also gave me some diamond earrings. Then he took me out to dinner and we ate fish. Then we went to Sears and we bought bullets.

The first time we went to target practice, it was on a levee, and we were shooting at little Bud bottles, and I hit it right on the nose, first shot. I was an ace. And from then on I beat all the boys. Being a good shot was pleasing. It wasn't a surprise, though. I think it's easy. Guns are sort of like pool to me; if you can just do it and be very good at it in front of a lot of people, it's fun, I don't want to hurt or kill anything, but I do like it. I like to be good at it. I mean, who wants to be a shit at anything, right? It's better to be a natural.

I don't really know why David gave me the gun. Maybe he knew he was going to take me somewhere where I would need it, Maybe he thought he could impress me, show me that I was in for a lot more than just a romance. We did take a trip down the Amazon not long after that. That was our first trip together. It was a test.

In the city I hide the gun. I keep it in trunks, and I keep no bullets near it. It's hidden away. I don't want to be killed by some junkie with it or have to hit somebody over the head with it. Keeping it loaded would be crazy. I’d shoot myself with it, or some baby would shoot itself. Some innocent child visiting on Avenue B …

I think it's legal for me to have it, but it damn well ought to be illegal, ‘cause it’s a sharpshooter's dream out any New York window. I don't take it out and play with it or anything. If I did that, then I'd probably want to start shooting. See, that's the fear. The fear is that you'd want to start doing target practice, trying to find an empty lot in New York or something. Which would be just stupid, right? 'Cause it's only fun to shoot it. You want to shoot it. If you did, then they'd all pull out their little pistols and have a shoot-out.

They're always fighting out there on the street. It’s very "drug" in the neighborhood, One time we came back from a tour and there were four men with rifles and Madras Bermuda shorts--they didn't really look like cops but I guess they were, some kind of special forces doing a drug bust--and that time we ran away because we were right in the middle. They were on either side of us, aiming right past us. But I hear shots all the time. One time we heard three shots, and we saw them take a body out of the heroin place down the block and put it in the trunk of a car. A couple of people died.

"I fired two warning shots in the lung, and one in the liver."

Dr. Richard B. Drooz, a noted Manhattan psychiatrist and teacher, foiled armed robbers at both his offices and his home before deciding to apply for a New York City pistol license.

I am that rare individual, a New York City pistol-license holder. I came to be so after the second attempted robbery, in 1967. The commanding officer of the l9th Precinct police came over to inspect the shambles that my fight with the robber had made of my place before the cops finally showed up, said that he'd never seen such devastation, and asked me, didn't I have a gun?

I said no, I didn't have a gun, and he looked at me as if I were sort of crazy, and said, "Doctor, how long have you been living here in New York City?"

At his suggestion and urging I applied for my pistol license. After a year and a half of all kinds of delay and harassment and so on by the license division of the New York City Police Department, famous for delay and harassment, my license came through, and I've held it ever since.

I carry the gun when I'm abroad, out in the streets, and I personally believe that anybody who takes the trouble to obtain the license has a certain responsibility to have the gun available for the defense of himself and of other people. My own gun, I know, has served to help some other people besides myself.

Incidents do happen. On one occasion, I was driving back to the office late one morning. My teaching work is in Brooklyn, in the heart of the most crime-ridden area of New York City, and I was stopped behind a line of cars at a light. As the car at the head of the line started to move out while I was still obstructed from the front, the door of my car was suddenly ripped open, and a young man pointed a gun at my head and threatened to kill me. He was backed up by two others, one with a knife and the other with what was apparently a toy gun.

I had my gun cross-draw under my coat, and I drew and fired.As I like to tell it, I fired two warning shots---one in the lung, and one in the liver.

The young man in question did not die, although he made a deathbed confession. I must tell you that subsequently, he was extremely nasty to the hospital personnel, and threatened to come back after his release and burn the hospital down. A suspicious fire did in fact start at the hospital shortly after his release, and I received a rather crude message from the staff, the tenor of which was "Why didn't you kill the sonofabitch?"

The gun I carry, and the one I used in the incident in my car, is a .38-caliber Chief's Special, stainless "snubnose." I have other guns, but this one, being a small revolver, is a comfortable gun to carry. Also it has a special sentimental attachment because it came from a lovely man, a very prestigious firearms dealer who was prominent in religious and community activities. One day his store was entered by a man out on parole from Elmira State Reformatory, who just in cold blood killed him and gave his brother a depressed skull fracture.

"I want people to know I have it."

Deanne Peterson works as a bartender on the Queen Mary in Long Beach, California while studying international politics. She owns a .38 Special Smith & Wesson revolver.

I got the gun when I moved from Grand Rapids, Michigan, to Chicago. I felt that having it gave me a necessary sense of security. I took my father with me to get it. He knows all about guns, so it was like having my own in-house expert. We wanted to make sure that it was a gun I could handle, but that it would stop an intruder, which is what it was for.

It's pretty, huh? I keep it all shined up. It's a fun little gun to shoot; it has enough of a kick that I feel like I'm really shooting a gun, it isn't like a .22. They tried to talk me into an automatic, but I didn't feel comfortable with it. When I pull this trigger, I feel like I really have to pull it to get the gun to work. And it's easy for me to load.

When I came here from Chicago I didn't bring it with me at first. I knew I shouldn't bring it on an airplane. But then I went back for my furniture, and brought it with me. Once I had it, you see, I didn't feel safe without it. I go out to the range and shoot it about, oh, once a month. I keep it loaded with hollow-point bullets.

I'm very open about having the gun. I want people to know l have it. I would hate to have my friends think going to pull a prank on me and crawl in my window some night, and have me shoot them. People do like pull pranks, and I seem to have friends who have that kind of sense of humor… Otherwise, people are curious about it. They want me to take it out so they can look at it.

I keep it in my bedroom, but I move it from place to place in there. Sometimes it's under the bed, sometimes it's in a bookcase, sometimes it's in a drawer. I used to keep it in my lingerie drawer, of course. That's where women always keep a gun, right?

We had a Peeping Tom here, so I got the gun and cocked it and told him I had it, and I would use it. I'm more frightened of having someone grab me than I am of shooting someone. I didn't go to the phone and call the police; I know from experience that they don't respond as fast as you'd like them to in a crisis.

See, my first reaction was that I was really angry. I mean, you have to make a definite effort to look in these windows--there are bushes, and there's iron out there--and I knew that we'd never feel as safe as we once did in here. The guy left, but I walked around in here with the gun in my hand for hours.

In a way, my attitude frightened me, because I knew that had he come into the house, I would have shot him.

But really, the minute I know someone's in the house, I'm yelling, "l have a gun, and I'll shoot you!" And if they don't hightail it back out, that's as much of a threat as I need. I really don't want someone in my house that doesn't belong. I know I could be in trouble with the law if the person isn't armed, but I'm not real concerned about being convicted and sent to jail. Being a young female of two females living alone, I think I'd get off pretty lightly.

"This guy came out of the closet with a double-barreled shotgun."

Tommy Walker has worked as a professional boxer, a bodyguard, an actor, a children’s magazine publisher. He is pictured in his Chicago apartment with his brother’s .32 H & R revolver.

I've had to use guns a few times. They’ve saved my life.

I used to go collecting rent for this guy, and there was attempted robbery on me a couple of times. I used to wear a lightweight .38 Detective Special stuck in the back of my pants. One time this cat was shooting at me with a .22, so I got off a shot. Nobody got hurt, and it was cool.

Another time, I was in a foreign country, and things jumped off. There was a minister, myself, and some other people, and I was one of the people they were relying on. Basically, everybody was starting to lose their heads, and there were some people with handguns who were trying to stop us getting across to the other side where there was a plane waiting to take us away. I can't say that I hurt anyone, but I did get off enough rounds so that I got the people from the mission across and into the plane and to safety. I'll say this much: it was the Congo.

I've gotten a few bullet wounds. I've got spots on my arm and in my side here, where I was shot with a shotgun when a person was trying to rob me. At the time I had a Walther P38 on me. There was a lady from Arkansas that was twenty-seven years old and had eight or nine kids, and I used to go to the building with food for the kids. Well, this lady had a nephew who laid around on his ass and didn’t do nothing, and he knew I carried money, and one night he arranged for his friends to rob me.

So I was sitting on the couch with a kid between my legs, playing with kid and talking to the lady, and this guy came out of a closet that had a curtain in front of it, and when he came out he had a double-barreled shotgun. He said, "This is a stickup. Take out all your money and your jewelry and give me the dough."

I said, "Man, you're crazy. You're pointing that gun, and this kid is here!" All the time I was thinking that this gun was going to hurt me, because he was shaking. I had the P38 on my left side under my suede jacket, and the safety catch was on, so I was trying to figure out what to do, because this guy was going to hurt me.

I said, "Man, c'mon, let me move this kid," and I raised the kid up and got my jacket up and knocked the safety off and I pushed the kid away.

We were in a basement, and there was a pipe there with insulation around it, so when he fired the first barrel, all that white shit went in my eye, so I thought he’d blown my face open.

I rolled around and came up and got two shots off. The first one hit him in the leg and ricocheted up his hip, and the second one hit him in the side. He fired the second barrel into the wall. I went over and put my stuff to his head and flushed his cousin out, and somebody called the cops, and thank God, one of the cops who showed up knew me pretty well. The kid with the shotgun went to the hospital and he was all right, and the thing stayed off the record.

The bullet wound I got here in my leg was from a lady who decided that she liked me a lot and I was unfair to her. She came in and emptied a .22, but only hit me once. I didn't even know I'd been hit until I got in my car--l was pretty nervous--and felt the blood in my shoe. The round had gone into the bone end flattened out.

"Where the red dot is, that’s exactly where the bullet is going to go."

Jimmy Quenemoen and Susan Snyder live in Clearwater, Florida, where Susie runs a surplus store and Jimmy a diversified business. Susie is pictured with an AR-15 assault rifle equipped with various sophisticated sighting systems, and Jimmy demonstrates the art of rappelling forward off a building roof.

SUSIE: We built the buildings we have here--a chartreuse house, a purple-and-white house, and an orange-and-green camouflage house--and we're pioneers. It’s an all black neighborhood, and we are the only people who would have the nerve.

Of course, the people in the neighborhood know us, and know who we are, and we don’t get any trouble at all. Nothing-not even bottles or chicken bones or anything thrown into the property. The local cops know us too. Sometimes we go up on the roof of the building at night with the AR-15 and the laser sight, and sight in on the police cars. Those guys see that little red dot show up on their car, and they know: "Oho, that’s Jimmy!"

JIMMY: That's a great weapon. The AR-15 is a great little rifle, and the sighting systems make it just about unbeatable. That's the state of the art, right there. The laser on it projects a beam which puts a red dot on whatever you’re aiming at, and where that red dot is, that’s exactly where the bullet is going to go, right there in the middle of that red dot.

That particular type of laser has an interesting history. It was originally designed for the American 180, which is a drum-fed, two thousand-round-per-minute full-auto .22 built for police departments. It was a psychological thing; they wanted to bring it out and let the press hear about it, let it be seen on television, so that the bad guys would know what it was. If you were holding a hostage, and you saw that little red dot on your chest, you would know what was going to happen if you didn’t surrender. In three seconds your chest wouldn't be there.

Police departments didn’t go for it, though. They thought it was a cruel weapon, basically. I mean, you can put that dot on a cinder-block wall with the American 180, and just cut it in half. It’s like a buzz saw. Unbelievable. Small targets are just gone, vaporized.

With the laser on the AR-15, though, sometimes you don't even need to put the weapon to your shoulder. When I'm running assault courses, I can run into a building with four or five targets seven yards away, put the dot on the targets, squeeze the trigger a couple of times for each target, and just buzz right through that building. You don’t have to stop or anything--just do it at a dead run, because wherever that dot is, that’s where your bullets are going. It totally eliminates the business of lining up your rear sight and your front sight and the target, and it totally eliminates guesswork.

"At night you can find the target with the Starlite scope."

SUSIE: The laser’s only part of it, though That gun also has the Aimpoint sight, which is like a conventional scope except that instead of cross hairs it has a little illuminated red dot in the center of the sight Then it has the Starlite scope, too. That's a light-amplification sight; you can see at night with it. At night, you can find the target with the Starlite scope, get the red dot in the Aimpoint centered right on him, then flick on the laser and put that red dot right on him. Then, if you want to shoot' you've got him. And if you don't want to shoot, he knows you can.

JIMMY: The whole system is fairly expensive right now—though it's like pocket calculators and stuff, the price is dropping fast--but even so we sell quite a few of them. Mostly we sell to people with boats. Anywhere in the Florida area, you see, you have a problem with hijackers; the drug smugglers need lots of boats, 'cause they usually sink them when they've made one run with them and usually they kill everybody on board when they do a hijack.

People with big boats will buy a Starlite and a laser, then, and mount them on an AR-15 or a Mini-l4 That way, they can eliminate a very serious problem without even firing a shot. The people who are going to hijack them know what it is when they see that red dot on their boat, and when they see an AR-I5 or a Mini-I4, they know that those guns will punch holes in half-inch steel at seventy-five yards. So they just leave, see.

I've seen boaters come in who are totally against guns but the fear has overpowered them, they just have no choice. They'll buy the gun and they'll buy a couple of thousand rounds of .223 ammunition, they'll go out to the range and practice, and they'll put it on board. They have to,

SUSIE: Really. It Just started a few years ago' and it happens all the time. That laser and the AR-l5 are a real good deterrent, though.

It works pretty well around here, too. Jimmy gets out of his truck here with it, and probably a .45 too, and people know. They know Jimmy. He's a locksmith, and he's the only one who will go in this neighborhood after dark. They call him "Magic Jim."

"Happiness is a belt-fed weapon."

Dennis M. Peinsipp, a Vietnam veteran, runs Shooter’s Shack, Central Florida’s largest firearms dealership, and Counterforce Special Security, Ind., in Clearwater. He is pictured with a standard U.S. military machine gun, the M-60.

The M-60 machine gun is my favorite weapon. It’s belt fed. It hooks up to an ammunition belt, and it just flat gits it--twelve-hundred meter range, .308 caliber. That’s the way to go to war! Happiness is a belt-fed weapon.

It has to be belt-fed, see, because the machine guns you see on TV--you know, this little thing the guy has in his coat-are submachine guns, and they don't make it unless you're going to murder someone in a phone booth. That’s because the average submachine gun has a cyclic rate of between seven hundred and nine hundred rounds a minute, but it only has a thirty-round clip.

What that means is that you have somewhere between one and a half and two seconds of firepower before your clip is empty-zzt-zzt, it's over!--and the average trooper ain't bright enough to pick a target, shoot the target, and move on to the next one in that amount of time. The only full-auto that's worth a shit in the field, then, is a belt-fed weapon with a lot of ammo.

They found out about all that the hard way in Vietnam by giving everybody a full-auto weapon. That wasn’t a smart thing to do. Most of the guys were going zzzt, zzzt, and not even hitting anything, and there went twenty rounds. I think the number of rounds expended per kill in Vietnam was something like seventeen million. In World War II, where the guys had to aim, I think it was something like one-point-two million. That tells you something: you can't hit nothing if you don't look down the sights.

That was a mess in Vietnam, though. The new standard rifle, the M-16, was thrown into a combat zone without proper testing, and so it had problems all by itself. On top of that, the military took guys and trained them on the M-14 in the United States--made 'em sleep, live and die with this big, heavy hunk of machinery you could use as a baseball bat--and then put 'em on a boat, handed them an M-16 at the other end, and said, "Go to it, bozo-breath. Go kill some gooks."

The guys looked at this thing, and it looked like a toy. It was full-auto, it was all this plastic stuff, it was half the weight of the guns they'd been trained on, it had half the range of what they'd been trained on, and it shot a bullet that was half the size of what they’d been trained on. These guys didn't even know how to load the magazines properly.

So the M-16 got a bad reputation it didn’t deserve, and you still hear that around today. But most of the young kids coming out of the Army today they Iove that 16. I do, too—always have. You hear a lot of bitching from people who don't know any better about the capabilities of the .223 round it fires, but have they ever seen what it does?

It's that light bullet and those high velocities. We had an ARVN in our group in Vietnam who was shot in the back of the leg with a .223: the round went into his leg, came up across his body, and came out behind his ear. If he’d been shot with an M-14, he might have lost a kneecap.

That round had a lot more killing power than anyone ever credited it with, until the Russians adopted it. Then it was just dandy. That's kind of funny; the Russians accepted it, so it must be good. You hear a lot of that kind of crap in my business.

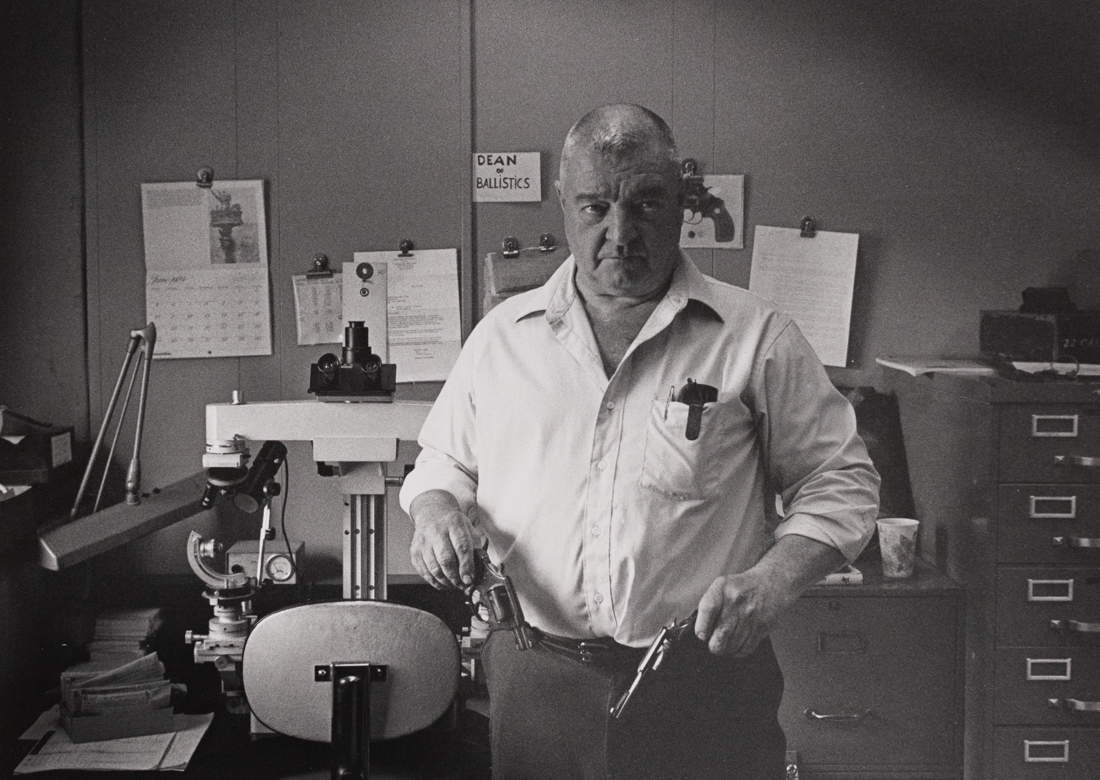

"The Carcano was a fake-out, a cover-up gun."

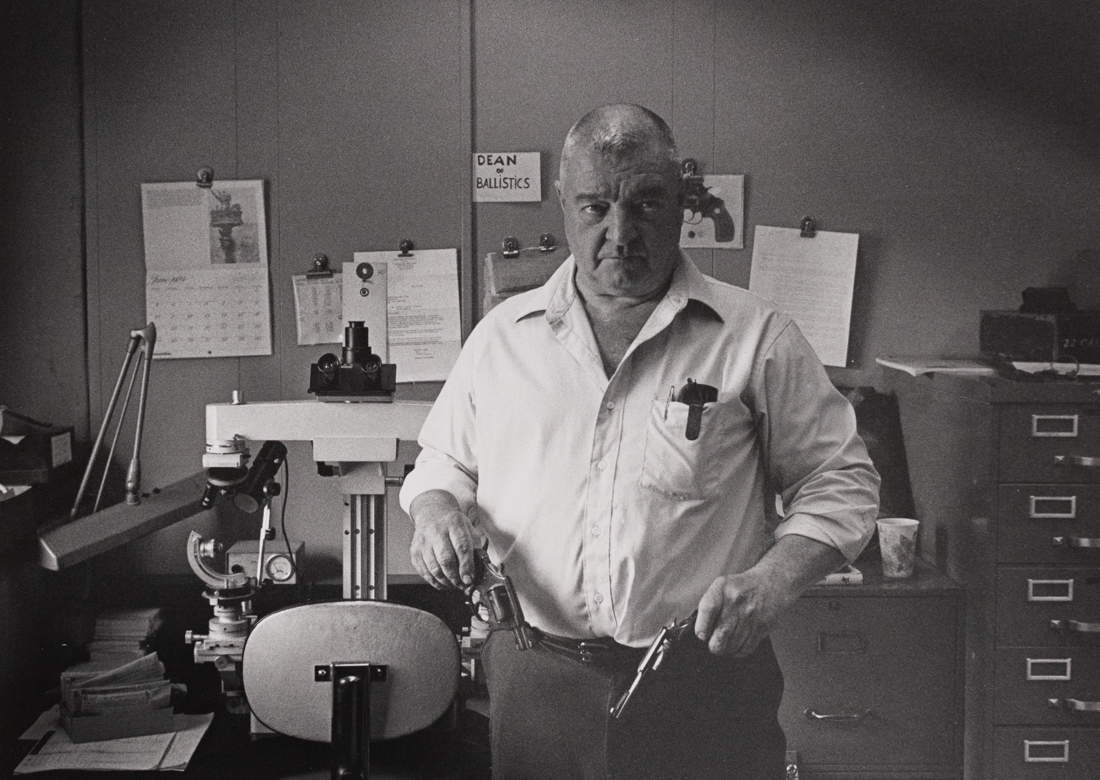

Rush Harp,

a pneumatics and firearms expert, described himself as an "assassinoligist" for the last one third of his life. He is pictured with a Carcano Mannlicher rifle, the type of gun used by Lee Harvey Oswald. Mr. Harp died suddenly in Woodstock, New York, some three weeks after he spoke to us.

The second day after JFK’s assassination, I knew there was a conspiracy, because the cops in Dallas had signed an affidavit saying that the gun used was a 7.65-millimeter Mauser with a 4-to-3 X 'scope, and they had identified it absolutely’ I figured that was right, because a Mauser would blow Kennedy's head off, because it’s some gun, it’s equivalent to our .30-06. Then, the second day—oho! --it was a Carcano Mannlicher like this one here, and hey, they had made a mistake. Now it was a 6.5 millimeter, and I said "No way!"

Then I noticed that in the description of the Carcano, nobody had found the clip. A Carcano Mannlicher will not function or repeat without a clip. With a Carcano, you push the loaded clip down into the gun, and as you work the bolt and fire five rounds, as the sixth round goes into the breech the clip falls out the bottom of the gun; there’s nothing to hold it in. But there was no clip in the gun, near the gun, found by the gun. There were three empty shells and one live round, which was still in the gun. That should have left two more live rounds in the clip, and the clip in the gun--but there was no clip, and no other live rounds. There were other mistakes, too, about where the empty shells were and what kind of 'scope was used, and also, we have a picture of the Mauser, after it was found, being held up on the roof of the Texas School Book Depository Building by the police. That was in the Dallas Cinema Association movie. So we know that the Carcano was a fake-out, a cover-up gun.

In fact, Kennedy was hit by four bullets. First, someone in front of the sign (this is all as seen in the Zapruder film) gets him in the neck with an umbrella gun from a range of about five yards. The idea of that was to paralyze him. I've got one of the rockets that are fired from the umbrella gun. I bought it at a gun show. It was a weapon designed for the CIA.

So in the Zapruder film you see Kennedy reaching for his neck; that's the puncture wound done by the rocket fired from the umbrella gun. Nobody carries an umbrella in Dallas, but in the film, on this nice sunny day, this guy whips out an umbrella when Kennedy comes along, and rotates it, aiming at the limousine, and--ah! —Kennedy’s reaching for his neck.

He stays paralyzed for the next one hundred frames of the film, then three bullets hit him within two frames. A pistol bullet hits him in the back at frame 312, and his head goes forward two inches, and then at frame 313 he explodes, because a shot coming in from over his cheekbone blows out the right side of his skull, and a shot coming from the Grassy Knoll blows out his occipital bone. My guess is that those two shots came from .30-06-type rifles firing scintered uranium bullets, which weigh sixty percent more than lead bullets and are totally frangible. That’s why, in the X rays of Kennedy's brain, you have thirty or forty "stars," which are little tiny bits of metal. No normal bullet is going to do that.

"We Japanese are always fascinated to see guns."

Rocky Aoki,

the multimillionaire owner of the Benihana restaurant chain, has been a champion wrestler, powerboat racer, and intercontinental balloonist. He is pictured in one of his homes with part of his gun collection.

I used to collect guns. I collect anything. I have Indian art, I have Japanese and oriental antiques. I collect stone statues--I love stone statues--and I have many lions' heads in the house and outside too. Right now I have maybe five Ferraris and eighteen Rolls-Royces of all kinds. I used to collect restaurants, too--French restaurants, Indonesian restaurants, other kinds of restaurants--but then I changed to just collecting Benihanas. I also used to collect antique Japanese guns; then I started to shoot, so now I have old guns and new guns too.

But I don't collect all these things anymore. I have so many things that I don't want to own anything more. Talk about airplanes? I have four different kinds of airplane, and I don't even fly. I have a pilot sitting in the Miami house doing nothing, because I don't fly. I don't want to waste my time and money, so I don't collect things anymore.

That's why I didn't renew my New York gun permit. As a matter of fact, I had a permit to build a pistol range in the garage, but the garage burned down, so everything went kaputo.

I used to carry a small gun on my leg, though, inside my boot, because I'd rather kill a guy than have him kill me. When I had just three restaurants in New York, I collected cash from Benihana West, Benihana East, and Benihana Palace--but since I don't see the money anymore, I don't have to carry a gun. I have a driver to pick me up and take me anywhere I want to go, so I am very safe.

Back when I had a smaller operation, I wanted to protect myself. If somebody stuck me up, I would have been the first guy to give everything I had: that's why I used to wear a lot of gold around my neck and on my fingers--to have something to give. I thought of the gun in the same way: if something happened, I wanted to survive. I wanted to live. I have survived so many accidents--in my car, in my boat, even an airplane crash a long time ago--so I know about surviving, and now I feel that I can survive without the gun.

I like small guns because I am small. The gun I used to carry was a Browning .25 automatic. It shoots well, that gun. It's very powerful. It hurts a little bit, but it's a challenge: with a small gun, you have to have a technique to shoot well.

In Japan, all guns are prohibited. Only policemen have guns. That's why we Japanese are always fascinated to see guns. One of the reasons I collected them was that fascination. In Miami, you know, you can just buy a gun if you are a legitimate person and you have the right identification.

It's amazing. Now, I have over a dozen guns: back in Japan, I never even saw them.

Lots of Japanese friends of mine come over here, and the first thing they want to do is shoot. It's the first time in their lives that they've shot a gun! It is such a pleasure for them.

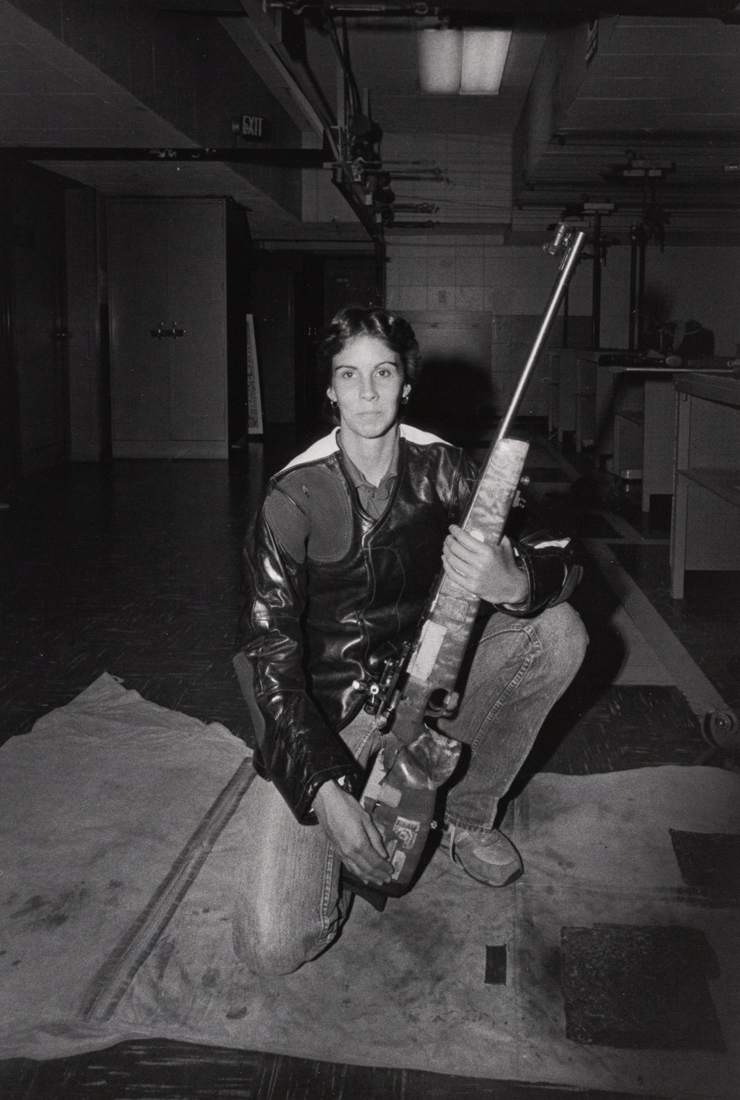

"You ask a kid, 'Do you want to go shooting?' It's, 'Oh, yeah!’"

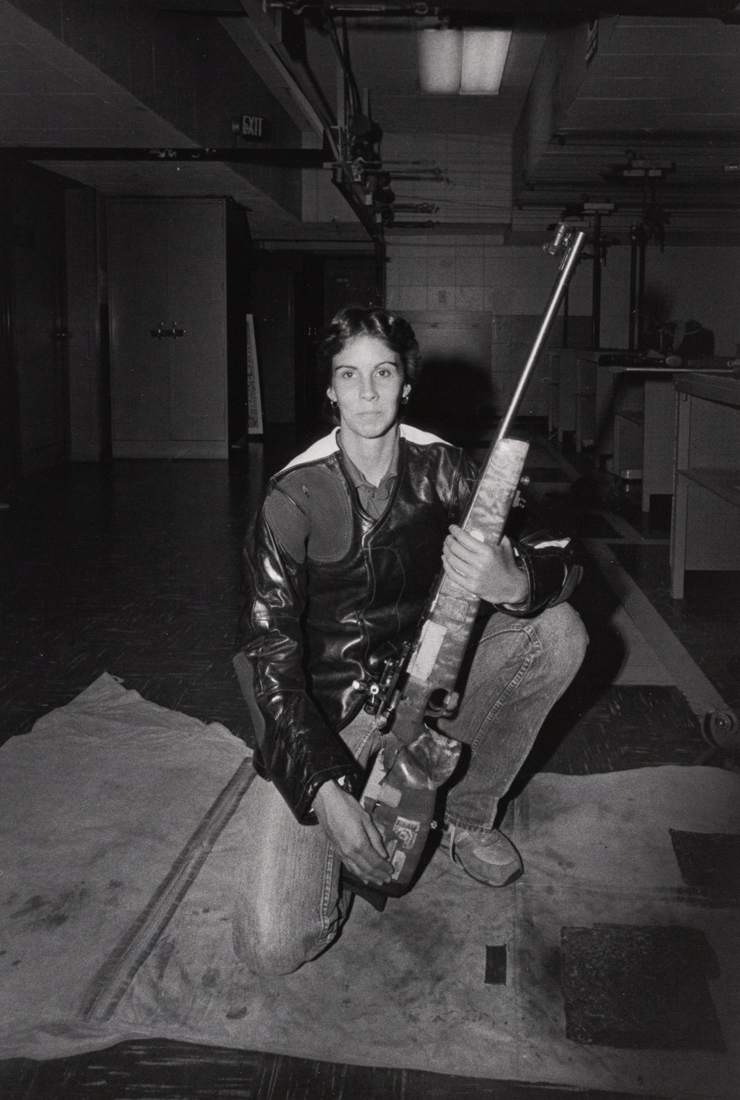

Marsha Beasley is a U.S. Champion smallbore rifle shooter and is Junior Programs Coordinator with the National Rifle Association. She works to develop and promote youth shooting programs in the United States.

In competitive rifle shooting, it's not so much the amount of time you put into it as the quality of the time. It's been said by several top coaches that how fast you progress is directly related to your ability to analyze your shooting, to think about it. This is in contrast with a sport such as weight lifting, in which somebody who does enough lifting and strength training—practice--will progress. In shooting that's not true; it all hinges on how well you think about what you're doing.

People have varying natural talent for shooting, of course, but it is a sport which can be learned. All you have to have is correctable eyesight. Then you have to learn how to hold the rifle steady enough to shoot a ten, you have to learn how to read the wind, and you have to develop the mental skills--basically concentration--to be able to repeat each action time after time in a match situation. Once you do all that and you get really good, you're basically shooting for perfection, in the standard .22 rifle prone event, where you shoot sixty shots at a ten ring less than half an inch in diameter fifty meters away, the world record is a 598 out of 600. There is just no room for mistakes.

More women are getting involved in shooting, partly because three Olympic shooting events for women were added in 1984. Also the NRA is looking for ways to make the sport more accessible to females. Right now, the average junior program has about 20 percent females--but why is that? Is it that girls don't want to shoot, or is it that they've always been told that they don't want to? We would like to move it closer to fifty-fifty.

This is a great sport. It offers opportunities most other sports don't. As I said, it requires learned skills and doesn't depend on body size or weight or strength. Shooting is a very safe sport. Additionally, it's not one you have to abandon when you turn sixteen or thirty; it's very much a lifetime sport. It offers team camaraderie as well as solo competition, and in addition to sport, develops great things like discipline and concentration, that kind of thing.

There are about two thousand NRA-affiliated Junior Clubs, which is how most young shooters get their start. I started shooting at age eleven at a junior club, but if there hadn't happened to be a club four blocks from my parent's house, I doubt I would have ever gotten involved in the sport. I'd like to see clubs that offer youth shooting Programs in every community in the United States, so that every kid growing up would have the chance to learn to shoot.

It is a shame there are not more adults interested in organizing junior clubs, because I think that kids are almost innately interested in learning to shoot, or at least trying it. If you ask youngsters, "Do you want to go shooting?" without exception it's "Oh, yeah!" That's how it's been with every kid I’ve ever asked, boys and girls too. People just love to shoot, and they really should get the chance.

"IPSC shooters are the most proficient gun handlers in the world."

Mickey Fowler progressed from motorcycle and automobile racing to International Practical Shooting Confederation and NRA "action shooting" competition. He is a three time Bianchi Cup winner and a U.S. National Combat Champion.

The appeal of the sport is that whereas most formalized handgun competitions use the same course of fire every time, with the same point total to shoot for, IPSC shooters are constantly given new challenges; it's a new match with a different course design every time. This means that IPSC shooters are the most proficient all-around gun handlers in the world. They learn it all: how to draw the gun quickly, how to hit a small target quickly, how to reload the gun quickly, how to shoot running, sitting, strong-handed, weak-handed—whatever--from all kinds of positions at all kinds of ranges. A world-class IPSC shooter can't have a hole in his skills.

The word "practical" is in the name of the sport because the sport is somewhat related to real-life self-defense with a handgun. Some of the matches are built around simulated real-life situations that could actually happen. You shoot at cardboard, buff-colored targets which simulate a head and torso, the aim being in most cases to place two quick shots in a vital zone, and there are no restrictions on equipment; you use whatever you think is going to do the best job. The equipment we use nowadays, therefore, is a direct result of match design. A lot of the guns, for instance, have compensators. That's because compensators cut down on muzzle rise, which means that your second shot can be fired accurately a lot more quickly than it otherwise would. That also means, of course, that the guns we use in competition are not practical guns for self-defense; not many people would want to carry around a gun that has as many gadgets on and is as long as a compensated .45 Government Model.

Even though the sport is called "practical" shooting, then, it's basically a game. It flies completely in the face of sound self-defense tactics much of the time. If you used the tactics that win IPSC matches in a real-life self-defense situation, you'd be in a lot of trouble. On the other hand, the game does teach you to shoot a powerful handgun quickly and accurately, and that is no small advantage

The game really started catching on in a big way in the middle 1970s, and since then it's grown a hundredfold with all that entails. When I got started, the most you could hope to win was a gun; now, it's possible for a top shooter to win about fifty thousand dollars a year, plus equipment and contracts with gun and accessory manufacturers. The future of IPSC or "action" shooting lies with the companies outside the firearms industry, though, if it really takes off, it'll be because cigarette and beer companies and the like get involved. We're starting to see that now and also some regular media coverage. We're bucking a strong anti-handgun media bias, of course, but hopefully while the sport has a way to go before it achieves the dollar status of golf or tennis, it can surely get up to where we can be a full-time professional shooter.

"After a while, shooting becomes the only thing that's interesting."

Michael Bane began his journalistic career as a newspaperman. Innumerable div and book credits later, he now freelances out of Tampa, Florida.

I started shooting when I was about six. I shot with my father, and when I got older I went out shooting with my friends. That was in Memphis, and in Tennessee in those days, it wasn't that big a deal to shoot. You'd just go on down to any vacant lot and plink away; nobody thought that much of it.

When I went to college, then, it was a real shock. I got a job on the college newspaper right away, and on the first day they explained to me that to have the right attitude, you had to be "for gun control." Back in Tennessee, that attitude was nonexistent.

It was funny. I still had guns, but this was college in the sixties; I had a ponytail, the whole deal. People would come out to my trailer, look around, and say, "What's that?" I'd say, "That's a gun," and they'd go, "Oh my God! It's a gun!" Eventually I got a Huey P. Newton poster with the quote "An unarmed people are slaves, or subject to slavery at any moment." I'd just point to the poster, and that was okay: if Brother Huey says it's cool.

Having guns where other people didn't, and having guns but having no decent place to shoot them, continued until just a couple of years ago when IPSC-style combat pistol shooting started up here in Tampa. I was desperate to shoot, so I got involved in that, and for the past year or so

I've been doing it really seriously. I tried to do it haphazardly, but the only thing you can accomplish that way is creative failure.

The thing about shooting, you see, is that if you're serious about it, it tends to be an all-absorbing kind of sport. It's like you're a computer and it's filling up all your memory, it's eating up all your thinking time. And after a while, shooting becomes the only thing that's interesting. Your career isn't really interesting anymore.

In my case, I also have the problem that I'm a writer, and these are grim times for writers. The basic dynamics of the marketplace have changed since I got into it, and all the things which made it an interesting career just don't exist anymore. Now, it's like, "You want another div on some celebrity nitwit? That's fine..."

I have a sideline writing for the gun magazines these days, though, and that's fun. It started out as a joke between my friend Mac and me; we decided that we'd write for the gun magazines, because that way we'd get free guns. It seemed like a real good idea at the time. I can sell stories just fine, so I went to it, and now I'm "a gun writer."

At this point, if I could get away with writing just outdoor stuff, that's what I'd do--but the money's just not there. It's two hundred dollars or three hundred dollars an article, tops, so even if you write like crazy you can't do it. I never have gotten a free gun, either: the whole plan was a bust. My shooting's improving, though.

"I’ve found out through shooting that there’s more to life than work."

Mary Ellen Moore lives with Michael Bane (previous interview), and is also a writer by profession. She lived around Michael’s guns for ten years before taking up shooting herself.

As Michael said, he was involved in IPSC shooting very haphazardly at first, and that was really irritating to me. He was always last, and he'd come home and grumble. He started thinking about quitting completely, but he really liked the people he shot with and he really looked forward to the matches; it was only after he came home that he was miserable. We talked about it, and he told me that if I were doing it with him, he could really get into it and enjoy it more.

I went to one of the matches, then, and once I got over the hump of meeting the people--basically, I'm not very outgoing--I started to like it. For a long time I’d been a fan of the woman character Purdy on "The New Avengers" TV show. On every show they somehow, managed to fit in a sequence in one of those combat "fun houses," with Purdy going through the course in these weird long dresses and high boots, shooting "A" hits on everything, then blowing the smoke from her gun and putting it back on her hip. When I saw that first IPSC match, I thought, "That's just what Purdy does!"

I edged into it gradually, and now I'm really serious about shooting. In fact, shooting is the main reason I’m looking for a job right now when you’re a freelance writer, your time is never really your own, but with a well-defined permanent job, I can have my own hours when I'm not working, And with a regular paycheck coming in, I can help pay for bullets and new guns and matches and so on. I used to work all the time--all I did was work--but now, even though this sounds trite, I've found out through shooting that there's more to life than work. I’ll do my job really well, but I really don't want work to take over my life again, because I'd rather shoot than work.

I think that shooting has helped my self-confidence tremendously. Whenever I used to have to do something hard, I'd think back to when I had to appear on television to promote one of my books, and think, "If I could be on television without passing out, I can do this." Now, I think about shooting: "If I can get up in front of forty people every Sunday and humiliate myself in this strange sport, and come out of it still liking it, I can certainly go interview some housing developer somewhere."

Also, if I put the time into it, I can really see myself doing well at this sport on a national level. The top national IPSC woman shooter has only been doing it three years, she's in no better or worse shape than I am, and she had no more of an edge than me when she started. That's kind of exciting for somebody like me, who's never participated in sports in her life. Maybe, if I'm willing to work at it, I could be the top woman in the field.

"I waited for his two beady eyes to come out."

Tony Carlotto is co-owner of a photography store in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He also raises horses, pigs, and chickens.

Hard to say why I first started buying guns. I like western history and stuff, so I started buying the replicas.

Had a friend who was a dealer, and he had a few. I saw how they looked; they looked pretty nice. That’s how I saw the .44-40. It’s an 1875 Remington replica, and I got that. Then I saw the .357, and it looked pretty nice. Now I’ve got about twelve or so.

I use them for playing. Go outside some days and blow up five hundred hounds. Shoot beer cans, pails, raccoons. Usually with coons it’s three o’clock in the morning and the neighbors are wondering what’s going on. Last coon was a big one, in the bard. I’d just got a new gun, that little Bernardelli. Never fired it till then. I went up to the barn and the coon got out the window. Come back, and I was laying in bed and I hear the chickens going crazy, so I went back and he’s eating all the eggs and he’s got a couple of them inside there, so I waited for his two beady eyes to come out, and let loose with it. Worked pretty good.

At first I didn’t have the heart to shoot coons, but after they started destroying everything—probably cost me two or three hundred bucks’ worth of feed and vitamins and that—I started getting mad. Then this last one shit on my power saw, and I said, "That’s it, there’s no more heart for them."

My favorite gun is that 1863 Springfield rifle there, black powder. That’s a lot of fun. I bought it one day, took it out and fired it. Then I did it twice more so I got to like the idea. Plus it’s inexpensive to shoot, plus the history involved in it. There’s Civil War history in it, western history in it.

I like the .357 too. Use it for plinking around. Expensive way to do it, though—twenty bucks for fifty shells.

Plinking’s great. My cousin comes over and he’s got a 22-pump just like that Winchester I got, so I’ll let me shoot a lot of my rounds. Chicken eggs once in a while from the porch. I got one on the first shot once; figured that wasn’t too smart. We figured it’d take us about 25 rounds, and I got it first shot. Just to make it exciting one day I took a Playboy centerfold and shot the tits, right through the nipples from a hundred feet with a ‘scope on it.

I’ve never been in trouble with guns. I got shot in the ass with a pellet gun once when I was a kid, but that’s about it. We used to have wars with BB guns, wore winter coats in the summertime and the pellets would bounce off, but this one kid had a pellet gun he could cock up about twenty times so it was real powerful, and he got me in the left cheek. I only found it about two months ago ‘cause it was starting to come out. Well, actually, it was my wife who found it.

"It’s one of the last freedoms we have in this country."

Kurt Hermann, a New York advertising executive, lives in Connecticut. One of the guns he owns is a one-hundred-seventy-five-dollar mail-order replica of a .45 Thompson ("Tommy") gun. Federally designated a "non-gun" the Thompson will not fire.

Anything that's unique appeals to me, or something that nobody else has. How many people around here would have Thompsons? I’d say there weren’t any. I feel this makes me unique, like the car that I drive, the clothes that I wear, the audio equipment that I buy and use--everything. I feel that I'm an individualist.

I throw parties here every year, and we were going to have a 1920s speakeasy party with the clothes and the records and everything, and I thought that definitely I had to get a machine gun. I was calling on an agency, and the gal had to excuse herself. She had a Sharper Image catalogue on her desk, and I was flipping through it while I was waiting, and there it was, the Thompson! So I grabbed the phone and I called and ordered it on my Visa card, and by the time she came back and said, "What are you doing?" I just said, "I just called and ordered a machine gun." Haa! That’s how it all started.

I always wanted to get one of these, because I like the historical conversational value it has. It’s not something you normally see in somebody's living room when you go over to their house.

The first reaction is, "Is it real?"

I sort of go along with it. I say, "Of course it is. Why?" They say, "Isn’t it illegal?"

"Not in Connecticut."

"Oh, really? Does it fire?"

"Yeah. I take it to the range once in a while with friends and we all fire it."

Eventually I let them in on the fact that it’s replica and I have it just because it played a big part in our country's history in the twenties.

I think that was an interesting period. It was a very tragic period. I'm not supporting that period, but I think the costumes that they wore, and everything else, were interesting, like other periods in our country and the world. The killings and the murders that went on were very tragic not only to the people who were involved--their own group, "The Mob', as they called it--but also the innocent people that got in the way accidentally,

Sometimes I pick the Thompson up and look mean and pull out one of the records from the era and imagine what it was like.

I would have been a federal man. In fact, when I was Iooking at careers I was considering the FBI. That changed because my father was a major influence on me getting into advertising, but I was very serious about joining the FBI.

I'm an NRA member because I think it's one of the last freedoms we have in this country, and if they take that away from us we have nothing. If the Soviets knew that Americans didn’t have guns in their homes, they would find a very easy way to get in here. As Iong as everybody has a weapon in their home--or at least the Soviets think we do—they have no chance over here. That's one of freedoms in the strength of our country.

"There was a hole through the wall that was really kinda large."

Jack "Cowboy" Clement is a Nashville record producer/songwriter whose clients include Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings.

I was in the Marine Corps, you know. Got an "Expert" marksmanship badge, which ain't that easy. I was classified as an MP and was on the drill team, so I had three weapons: a .45 pistol, an M-1 rifle, and an old Springfield '03 with a chrome-plated bayonet.

The Springfield was better balanced for drilling than the M-1, see. You could flip it in the air with the bayonet on. I perfected what I called "the double toss": the rifle would flip twice, then come down with the bayonet sticking in the ground. That would bend the bayonet, of course, but you could bend it back. When they chrome-plated them, that took the temper out of them, see. I had a lot of fun on the drill team.

The .30-30 I have now is a nice gun, but I don't shoot it much. The elevator on the sights is missing, for one thing. I found that out one night when I decided it was time to try it out. I'd had it a year or two, and I had a few rounds, and I thought it would be perfectly safe to squeeze off a few here in the house if I got me a proper backdrop.

I looked over at the door. It was an unnecessary door, and I hadn't gotten around to tearing it out, so I decided to write myself a little note to remind myself about that by blowing the shit out of the doorknob.

I went and got my gun and loaded it up. I squeezed off a round into the floor just to make sure it was working, then I got away from the door a bit, lined it up real good, and squeezed it off. You don't jerk the trigger, you know—you squeeeeeeze the trigger. You got to line 'em up and squeeeeeeze 'em off.

I fully expected to see that doorknob just disintegrate before my eyes, but it didn't, so I thought, "Well, I'll take a little better aim." I lined it up again and squeezed off another one, but still nothing happened.

I decided to go down and take a look. I saw that the grouping was pretty good; it was just low. Then I looked at the gun, and sure enough, the little elevator on the sights wasn't there. No wonder I was shooting low!

I went back to the door, and oho, I'd done shot through it. I went looking for holes. There were holes out the back of the door--those were a little bigger than the holes in the front--and then there was a hole through a wall that was really kinda large. Then I noticed that the radio on the receptionist's desk was shattered, and beyond that was a hole through the front window, going out toward houses where a bunch of kids were sleeping and stuff. Oooooooooh

Anyway, I decided, "No more squeezing off rounds in the house." I've still got a nice little .22 around here, though and I can hit some things with that.

"Fokker knew that it would work, but the bigwigs wouldn’t believe him."

Cole Palen, pictured with his flare gun beneath the muzzle of the twin Spandau machine guns on his World War I Fokker Triplane, is the proprietor of the famous flying circus in Rhinebeck, New York.

In the beginning, when a Frenchman and a German met in the sky, their paths were just crossing as they flew over each other's territory, trying to find out what was going on. They would wave to each other, because they were sharing the excitement and beauty of flying. They were well fed, and they wore the best uniforms and flew the best planes, and that was the way to fight a war: just wave at your enemy.

The fighting started one day when one pilot, instead of waving, thumbed his nose at the other guy. The next time they met, there was a pistol; then there was a rifle, then a machine gun firing out to the side of the airplane, then a machine gun fixed to the top wing and firing over the propeller.

Some of those early rigs were something else. On the British FE-28, for instance, which was a "pusher" plane, the gunner had to use one gun for shooting ahead; then climb up over the pilot to another gun mounted on top of a ladder whenever they were attacked from behind, then climb back to his seat.

Then along came a poor daredevil stunt pilot flying for the military, one Roland Garros, who realized that if he could fire the machine gun straight down the line of flight of the airplane, he wouldn't have to fly in one direction and shoot in another: he could just aim the whole airplane. He thought about it, and came up with a way to do it. He mounted the gun behind the whirling blades of the propeller, to the back of which he had attached triangular steel plates, and fired: some bullets few out between the blades and the ones that hit the blades simply bounced off.

For a few weeks, Garros was the terror of the skies—but firing the gun into the propeller blades was like hitting them with a sledgehammer, though, so finally his propeller broke, and he had to glide down and land in a meadow. And since the hunting had been so much better over German-held territory than over French, all the people who ran up to his plane were speaking German.

When the Germans realized they had captured Roland Garros, the Terror of the Skies, they sent all their best technicians to inspect his plane and find out how he did this marvelous thing. One of those Germans was Author Fokker, one of their leading aircraft designers. He laughed when he saw the little plates on the blades, and within forty-eight hours came up with a mechanical means of lining the engine to the machine gun. All the parts within an engine are connected to other parts with gears or connecting rods or cams or push rods or whatever, and everything is precisely timed, and Fokker just extended this back to the machine gun: when a little cam connected to the engine came up and said "Don't shoot,', because the propeller was in the way, the gun didn't shoot.

Fokker knew that it would work--it was so ridiculously simple--but the bigwigs wouldn't believe him. Even though he was a civilian, they made him go up in a plane and prove the synchronization gear worked by shooting down an enemy plane. Fokker went up, but he couldn’t do it, so they got their ace, Max Immelman, to try it. It worked fine, and the Germans ruled the skies until the Allies found out how the synchronization gear worked. Then the dogfights really got started.

"It's better than anything the Russians have."

Captain Tony Parker is a flight instructor on the F-16 the United States Air Force’s frontline combat fighter aircraft. He is pictured at MacDill AFB, Florida, as armorers load 20-millimeter cannon ammunition into his fighter.

Basically, a fighter aircraft is a flying gun, and that hasn't changed much. The F-16 is a flying weapons system configured for air-to-air and air-to-ground combat with a variety of weapons, but for close-in fighting and strafing it relies on its gun.

That's something we learned in Vietnam. Initially, our F-4 fighters did not carry an internal gun. Unless they were carrying a gun pod, they had bad problems with MIGs that got inside the range of their missiles. Now, all U.S. fighter aircraft are produced with an internal gun.

The gun itself is an old weapon--it's the same six-barreled 20-millimeter cannon that's been in service since the late 1950s--but it does the job. Its maximum rate of fire is six thousand rounds a minute, and you really don't need more than that. That's a hundred rounds a second which can be put into a very small piece of sky, and one 20-millimeter round in the right place will have a very negative effect on any airframe. The F-l6 carries enough ammunition for about five very short bursts.

The gun is very reliable; it's a proven weapon, and in combination with the F-16's computer sighting system it's pretty definitive. The computer is the key to it; it cuts out a lot of guesswork and reduces the margin of error substantially. With this system, once the sight is punched up in visual display and the radar is locked in on the target, the computer makes a lot of calculations that previously had to be made by the pilot. For instance, it calculates the range of the target, the G's the target is pulling, the G's your own aircraft is pulling, and the gravity drop of the rounds once they're fired.

Basically, the computer makes sure that the rounds actually arrive exactly where you aim them--right on the target in a tracking shot, ahead of him in most other shots—by compensating for the various motion factors working against that result.

The computer does that very well, too. Vietnam-era computer gunsights had to make assumptions about movement which were not necessarily true, but this is new technology, and when the radar is locked onto the target, it doesn't make assumptions. Instead, it instantly collates observed data on what's actually happening, so that what you see is what you get. It works very well indeed, even without a radar lock.

This whole weapons system, in fact, is really great. It’s the best there is. This is it, right here: this aircraft is the most sophisticated, most maneuverable fighter in the sky. It's the premier fighter of the Free World, and it's better than anything the Russians have.

That feels good, of course, but really, air-to-air combat hasn't changed that much. The other guy can still make unexpected moves, and he might survive your hits and come back at you, or his wingman might be working on you at the same time--all those factors are still operating in a dogfight. American technology gives us an edge, but it’s not a guarantee by any means.

No, it's still hairy, even with the F-l6. The pilot still has to make an awful lot of fast, correct decisions under a lot of pressure. That's why fighter pilots have to be such aggressive, competitive people. When it comes down to it, the guy who gets the other guy in his sights is still the winner.

"My gun had become a topic of conversation all over the world."