GEORGE W. GARDNER:

Archive of America 1960-1988

“America is my place.... I have no choice, and I have always felt that. Anyplace else, I’m just a tourist, I don’t connect. In America, I feel as if I have some deep notion of what’s going on. I am trying to get at what I think about America. I can feel this country.” -- George W. Gardner

The Andrew Smith Gallery, Tucson, Arizona; Deborah Bell Photographs, New York; and Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc., San Francisco, are pleased to announce their exclusive representation of the American documentary photographer George W. Gardner (b. 1940). Comprising thousands of photographs and tens of thousands of negatives realized largely between 1960 and 1988, his far-reaching work, truly an “American document,” reveals his deep empathy for the American experience, from the most ordinary moments of daily life to events that have shaped American history.

"I average about three hundred per season when their fur is prime.” Ray Milligan, pictured c. 1983 with his three children and his Savage over-under 22/20-gauge combination gun, is a professional fur trapper based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. (GG-GP-004) From Gun People, 1985.

Unlike more famous documentary photographers whose subjects were chosen by editors and others as generally being newsworthy, Gardner worked as an independent photographer choosing his own subjects and building up views of regular daily life. In this way, Gardner created a unified visual archive that defines and encompasses the American experience.

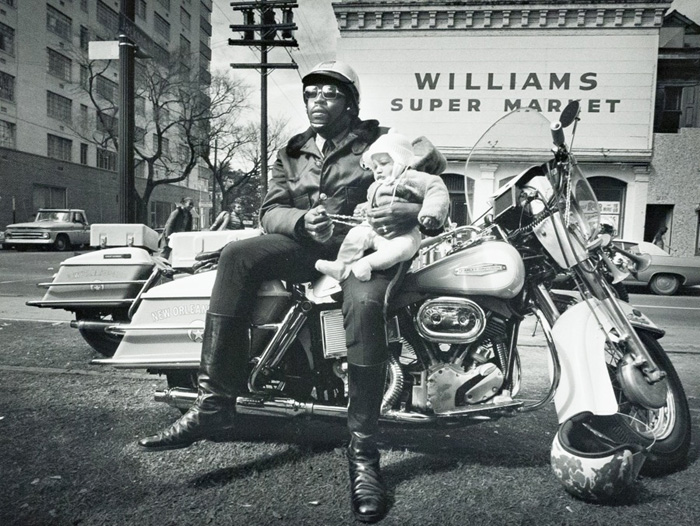

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1977 (GG-AI66-02)

Gardner was of the generation of documentary photographers who used Leica cameras, bought film in bulk, and shot daily and monthly using tens to hundreds of rolls of film. His extensive archive of negatives and contact sheets serves to exponentially enlarge the context for his finished work.

Piloting his own plane, or more prosaically traveling by car, he has traversed America many times, primarily from 1960 to 1987, to assemble the body of work that exemplifies his unique view and acute observations of the people and institutions that make up America.

Gardner understands the American experience, and how rural life has shaped our relationship with industry, technology, and diminishing natural resources. He knows how Americans work to live, and his vision cuts across and through cultural and economic strata. He comprehends the American dream as few artists do, probably because he shares it to an extent himself.

George W. Gardner was born July 22, 1940 in Albany, New York. His parents separated when he was four, and he was brought up by his mother. In order to protect the chickens his mother raised at their home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Gardner learned to trap raccoons and other wild animals. In high school, George took his only photography course, a brief formal introduction to photography. After high school graduation, George headed for the woods, where he spent the winter as a trapper. "Trapping is pretty grim," he says. "Ain't no way to live. So, I finally decided I would take photographs of animals instead of killing them. I remember seeing pictures in magazines, outdoor magazines of the sort we don't have anymore, and I said to myself, 'That's easy. That guy got paid ten bucks for that picture.' I figured I would do pastorals and hunting and fishing pictures, and it would be an easy way to make a living."

Gardner enrolled at the University of Missouri in 1960. Although initially attracted by the reputation of the school's photojournalism courses, he decided to major in anthropology. He learned his photography by doing it. As a freshman, he applied for a spot on the yearbook staff; asked if he'd done yearbook photography in high school, he lied and said "yes." He became the yearbook photographer at $2 per picture, and subsequently photo editor of the college newspaper. "I realized that the photojournalism program would be a good thing to stay away from unless you wanted a job with the Topeka Journal or the Geographic, and I didn't see myself at either place. Besides, I was already doing pretty well."

Gardner won some 25 awards in the photojournalism school's own photography competitions, as well as the major portfolio award, two years running. The latter prize: a week in New York working with Life magazine.

After graduation, he began his career as a freelance photographer in Wilmington, Delaware. Although he accepted an occasional assignment, Gardner, never without a camera, traveled around the country photographing whatever he found interesting, which turned out to be almost everything. Photojournalist Bill Pierce once referred to him as the "gypsy photographer, roaring in and out of towns..., camera at ready."

Throughout the 1970s Gardner’s work was championed by Hugh Edwards, the legendary curator at The Art Institute of Chicago, and by the renowned photography historian, publisher and editor Jim Hughes who featured it in Camera 35, as well as in Popular Photography. Other important periodicals, such as Creative Camera, published his images. Gardner’s photographs were also included in the 1983 revised edition of Documentary Photography in the TimeLife series, alongside the photographs of Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand.

In the 1970s and early 1980s the Douglas Kenyon Gallery, the principal photography gallery in Chicago, exhibited his work and collaborated with him on his two main publications: America Illustrated and Gun People (where Kenyon appeared on the cover).

Published in 1982, America Illustrated shows us, as Jim Hughes, states, “an America most people lived in and few people looked at.” Quite simply, our nation revealed to us. Much has changed since 1982, but what his photographs depict remains familiar, providing us with a mirror of ourselves that is still relevant.

In 1985 the journalist Patrick Carr and Gardner published Gun People, a visual ethno-history combining interviews with environmental portraits of people involved with guns. Follow this link to view text and images from Gun People in this collection. This prescient landmark snapshot of the most controversial area of modern political, personal, and journalistic debate has only gained in importance and relevancy almost 40 years later.

Much of Gardner’s most important work revolves around universal themes

as well as the specific subjects described below.

America: Protests, Parades & Politics

Gardner documented legendary protests and parades, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s I Have a Dream speech on August 28, 1963; the Poor People's March of 1968; the first Earth Day in Philadelphia in 1970; the Hardhat Riot in New York, May 8, 1970; and the first Christopher Street Liberation Day on June 28, 1970, which marked the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots in New York City. He also photographed small local protests and strikes, as well as state and national political campaigns and events such as the Democratic National Convention of 1972.

Untitled, June 29, 1968 (GG-1968-015)

Untitled, 1970 (GG-1970-204)

Untitled, 1969 (GG-1969-106)

Florence Kennedy, 1972 (GG-1972-066)

America: Regular Folks / Private Moments

Regular Folks / Private Moments reveals Gardner in the role of the photographer as objective observer, an academic notion that was a major didactic point at the time in journalism and anthropology. In these photographs Gardner refrains from interacting with his subjects as they are engaged in private activities or with their personal thoughts.

Untitled, 1972 (GG-1972-300)

Carbondale, Illinois, March 26, 1960 (GG-AI29-02)

San Francisco, California, 1970 (GG-1970-114)

Central Nebraska, Rt. 30, June 1960 (GG-1960-019)

Hough Neighborhood, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967 (GG-1967-010)

Staten Island, New York, 1970 (GG-1970-232)

Dana College, Blair, Nebraska, 1970 (GG-1970-339)

America: A Sense of Place

Published in 1982, America Illustrated shows us, as Jim Hughes wrote, “an America most people lived in and few people looked at.” He added:

“I was seeing, clearly and possibly for the first time, middle America, which is all America: The America of Saturday afternoon high school football, concrete highways to towns named Fate, and undeclared wars featured on the six o'clock news. This was not Apple Pie America, nor Glamor America, nor Ugly America, nor Bloody America. This was America as it must be, and I was seeing it because a citizen named George Gardner was taking me there.”

Talbot, St. Louis, Missouri, 1967 (GG-1967-030)

Interstate 80 overpass, Patterson, New Jersey, 1972 (GG-1972-269)

Arlington, Texas, 1972 (GG-1972-238)

New Jersey, 1968 (GG-1968-278)

Queens, New York, 1976 (GG-1976-177)

Sunset Strip, Los Angeles, California, 1969 (GG-1969-254)

Dana College Blair, Nebraska, 1970 (GG-1970-342)

Lynchburg, Virginia, 1968 (GG-1968-086)

Untitled, November 8, 1972 (GG-1972-280)

California, 1970 (GG-1970-081)

Atlantic City, New Jersey, June 1968 (GG-1968-036)

Untitled, November 1968 (GG-1968-172)

America: Portraits

Gardner’s portraits reveal his profound engagement with his subjects and his deeply rooted connection to them. Whether they gaze openly at the photographer or indirectly interact with him, discreetly participating in setting up “the shot,” the photograph arouses the viewer’s curiosity to know more.

Mr. And Mrs. Kenneth Crumb, Marathon, New York, 1975 (GG-AI01-03)

Iowa, 1972 (GG-AI65-02)

Hough Neighborhood, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967 (GG-1967-001)

Hough Neighborhood, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967 (GG-1967-012)

Hough Neighborhood, Cleveland, Ohio, 1967 (GG-1967-021)

New York City, 1968 (GG-1968-134)

Cairo, Illinois, 1969 (GG-1969-144)

Adult Education class and teacher, United Front Activity, partially funded by Federal Government, Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-143)

Welch, West Virginia, 1968 (GG-AI04-05)

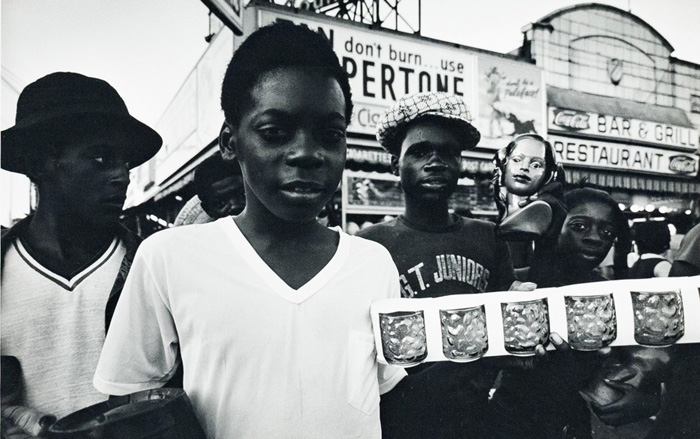

July 4, 1971, Coney Island, New York (GG-1971-112)

Untitled, 1972 (GG-1972-264)

Untitled, 1972 (GG-1972-255)

Photo Essays

Cairo, Illinois

A bystander to most events, Gardner did not hesitate to make plain his point of view when it came to racial injustice in America. Violent unrest destroyed large swaths of the Black communities in the Hough neighborhood of Cleveland, Ohio in 1966 and Cairo, Illinois in 1967, 1969 and 1972. These tragedies brought him to those cities to record the lives of the people left behind who had to pick up the pieces in the aftermath.

Cairo, Illinois, January 1970 (GG-1970-207)

Charles Cohen, Leader, United Front, Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-145)

Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-147)

Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-148)

In February 1972 Creative Camera published Gardner’s photo essay on the Black United Front, a group formed in Cairo to combat the violent attacks on the African American community by white vigilantes.

Gardner wrote:

“Cairo, Illinois is yet one other small, Mid-Western American town with one Main Street and a population one third of what it was in good old 1923. Half that population is Black, the other White and there is no grey. There is a great deal of shooting in Cairo. Whites shoot at Blacks and vice-versa. It is the first American town with the gun really louder than the rhetoric."

Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-151)

Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-152)

Cairo, Illinois, 1970 (GG-1970-159)

“I photographed Cairo -- primarily its Black community and the 'United Front', their 'Community Action Group' -- partially because I believe them to be right and partially because in America with it all one still realizes that Blacks can't get away with shooting White Photographers but Whites can get away with shooting anything."

The Mixer: Boy Meets Girl

Gardner’s captioned photo essay begins with these lines:

First Dates

The social chairmen planned

a dorm mixer at 3...

but some just came

to watch.

Slowly they gathered...

And looked...

and wandered…

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-001)

The gathering begins at three. By ten after, small groups of mutually exclusive boys and girls form and ignore each other -- mutually shy and waiting for the courage of large numbers, fast music but, eventually, a few bold ones emerge.

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-003)

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-009)

"The Cool and the Exuberant"

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-014)

"Persistence, as of old, pays off."

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-0017)

"Four Student Musicians -- and if you don’t dance you have to make clever

conversation; most dance."

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-0028)

"The first date is exploration; therefore, mostly talk."

College Mixer, Stephens College, Columbia, Missouri (GG-MIX-031)

"It’s quiet because they’ve gone back early."

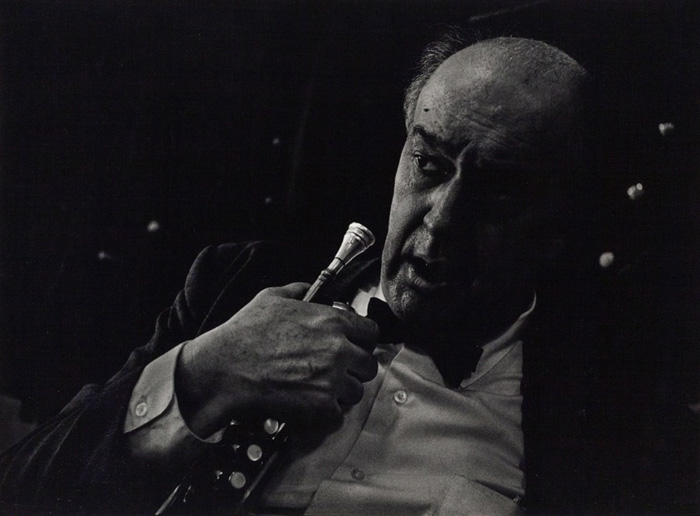

Blake Hobbs: The Music Man of East Harlem, 1966

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-01)

In this series George Gardner has captured the remarkable life and work of the beloved musician, teacher, and volunteer Blake Hobbs (1911-1973). Better known to local residents as “The Music Man of East Harlem,” Hobbs dedicated his life to fostering the artistic growth of this neighborhood.

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-02)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966(GG-HM-12)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-16)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-19)

“El Barrio,” or Spanish Harlem, as this section of Manhattan is often called, was home to large communities of Hispanic immigrants from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and elsewhere. It was also one of the hardest hit in the 1960s and 1970s, as New York leveled sections of the city for urban renewal and as the city struggled with deficits, racial strife, gang warfare, drug abuse, crime, and poverty.

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966(GG-HM-26)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-29)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966 (GG-HM-30)

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966(GG-HM-31)

Born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Hobbs graduated from Johns Hopkins University in 1933 with a degree in math. Soon after his arrival in East Harlem, Hobbs began working with the Union Settlement Association, a neighborhood housing, health, and advocacy organization, running the association's music school. Despite a dearth of funds, Hobbs found ways to bring music to neighborhood residents. He taught private and group music classes for children and adults and conducted a young people's orchestra. Under his leadership the Union Settlement Association's music school flourished. Hobbs also taught music in Harlem's under-funded public schools, often arriving in classrooms with a handful of plastic recorders.

Hobbs' commitment to East Harlem's community extended beyond music. He organized exhibitions of local artists' work, chaired the loan committee of the Union Settlement Association's credit union, and was involved in -housing, health, and other issues of local importance.

Blake Hobbs, New York City, 1966(GG-HM-33)

Gun People, 1985

Copyright 1985 Patrick Carr and George W. Gardner

In 1985 the book Gun People by Patrick Carr and George W. Gardner closely examined the vast scope of gun ownership, from the stereotyped individual who believes self-defense requires having a gun, to the many other people who may own guns, including the antique and rare gun collector, the target shooter, and the hunter.

The Gardner portraits, combined with the first-person interviews, create a highly charged document that now stands as the most important investigation of a large segment of the American population in the late 20th Century. It is unflinchingly straightforward in its photography and texts, examining guns, history, paranoia, fear, machismo, hubris, and common sense. With nuance and complexity, the book delves into the multiple viewpoints and controversies surrounding gun ownership.

Gardner did not approach his subjects for this project as an outsider. Both a photographer and animal trapper, he grew up in rural America where there was little controversy over the practical aspects of gun ownership. The results are consummate photographs whose subjects present themselves authentically, devoid of confrontational irony.

Dr. Richard B. Drooz, a noted Manhattan psychiatrist and teacher, foiled armed robbers at both his offices and his home before deciding to apply for a New York City pistol license.

"I carry the gun when I'm abroad, out in the streets, and I personally believe that anybody who takes the trouble to obtain a license has a certain responsibility to have the gun available for the defense of himself and of other people….

"On one occasion, I was driving back to the office late one morning. My teaching work is in Brooklyn…and I was stopped behind a line of cars at a light. As the car at the head of the line started to move out while I was still obstructed from the front, the door of my car was suddenly ripped open, and a young man pointed a gun at my head and threatened to kill me. He was backed up by two others, one with a knife and the other with what was apparently a toy gun.

"I had my gun cross-drawn under my coat, and I drew and fired. As I like to tell it, I fired two warning shots -- one in the lung, and one in the liver."

Marsha Beasley is a U.S. Champion smallbore rifle shooter and is Junior Programs Coordinator with the National Rifle Association. She works to develop and promote youth shooting programs in the United States.

"More women are getting involved in shooting, partly because three Olympic shooting events for women were added in 1984. Also, the NRA is looking for ways to make the sport more accessible to females. Right now, the average junior program has about 20 percent females -- but why is that? Is it that girls don't want to shoot, or is it that they've always been told that they don't want to? We would like to move it closer to fifty-fifty.

"This is a great sport. It offers opportunities most other sports don't. As I said, it requires learned skills and doesn't depend on body size or weight or strength. Shooting is a very safe sport. Additionally, it's not one you have to abandon when you turn sixteen or thirty; it's very much a lifetime sport. It offers team camaraderie as well as solo competition, and in addition to sport, develops great things like discipline and concentration, that kind of thing.

"There are about two thousand NRA-affiliated Junior Clubs, which is how most young shooters get their start. I started shooting at age eleven at a junior club, but if there hadn't happened to be a club four blocks from my parents' house, I doubt I would have ever gotten involved in the sport. I'd like to see clubs that offer youth shooting programs in every community in the United States, so that every kid growing up would have the chance to learn to shoot."

Bill Douglas has been collecting U.S. and other military guns since he was six years old. Professionally, he runs an insurance business in Dunedin, Florida.

"I have about fifty-five automatic weapons now. I've always enjoyed studying history, particularly the military and police history of the United States and the part that weapons played in it. You buy a gun, and you get a book to find out more about it, and it goes on from there.

"There'’'s all that, and then there's the design and engineering of the weapon, all the different techniques and developments. You try to put yourself in the shoes of somebody like John Browning, who was one of the most prolific gun inventors, and you try to figure out how he developed these weapons.

"The 'potato-digger' that I have was one of his guns, and it was the first gas-operated machine gun adopted by the U.S. It came about while he was watching some rifles being fired out behind his shop. There were some reeds nearby, and every time the rifles fired, the blast from the muzzles would bend those reeds back. That's when John Browning realized how powerful the muzzle blast was andstarted figuring out how it could be used to operate an automatic weapon. That was one of those moments which changed world history; and I have one of the guns that came from it.

"It's not as much fun as it used to be, though, because the value of U.S. military guns, particularly automatic weapons, is escalating rather drastically. In 1968, you secured machine guns out there, and granted a one-month amnesty. If you had an automatic weapon, you could bring it in either to surrender it or get licensed -- but after that there was no way to license such a gun. Today, if you find a German machine gun your uncle brought back from World War II, there is no way to own it legally. You have to turn it in for destruction or be liable for prosecution.

"That's something we all think about a lot. The machine guns legally licensed to collectors are almost never involved in crimes; the 'cocaine-cowboys' are using automatic weapons bought illegally and never registered, or they are buying semi-automatic assault rifles and then illegally converting them into machine guns. Unfortunately, the press doesn't usually make such fine distinctions, and legal machine gun owners end up lumped in with the bad guys."

Virginia Velazquez owns and operates two adjoining stores in the East New York section of Brooklyn. She received a National Rifle Association cash award for foiling an attempted robbery in February 1983.

"About three weeks ago, two men came in here. One of them had two guns, and he pointed them at my watchmaker. My watchmaker said, "Oh my God, it's a holdup!" and he started running through into the other store. I started running, too, but something came into my head, and I got my gun, and I ran through the other store and out onto the street and back to the front door of the jewelry store.

"One man was taking the jewelry, and the other was holding the guns. The man with the guns turned around and pointed them at me. He tried to shoot, but the gun he tried to shoot was old, and it didn't work. No bullet came out. I figured my life came before his life, so I started shooting. I shot five times and hit him twice in the head. Maybe I hit the other guy in the chest; I don't know. The first guy fell down, then got up and ran down the street, bleeding, with his guns. The Housing Police found him, and came here and said, "You had any trouble here?"

"I said, 'Yes. Why?' They said they had a guy hurt, and they brought him here, and I told them he was the one.

"They told me later that one bullet grazed his head, and the other one went in and came out again. He had a very strong head. When they took the X rays, they found out that he still had some shotgun pellets in his head from a holdup he'd done before. He was twenty-six years old, and he was on parole when he came to hold me up. They didn't catch the other guy.

"I was held up before. Jesus Christ, I don't remember, but it was about four or five times. One time, a guy came in with a shotgun. When I saw it was a shotgun, I ran.

"I've had the gun about a year and a half. Before that, we didn't have a license. My husband has a big gun, but he's not here when they do the holdups, so he got me the little gun. He taught me how to hold it, but I never shot it before I shot the guy. Now I'm going to the pistol range twice a week. I want to learn how to shoot well. It's nice. I enjoy it. It's good to learn, especially in this neighborhood. I like everybody, but when somebody tries to kill me...

"We've been here fourteen years, but it wasn't always bad. It started to get bad about six or eight years ago. Maybe it's going to get better. They're fixing up buildings and building new ones. My husband and I are going to retire to Puerto Rico in five or six years and build a mall in our hometown. It will cost about $250,000. It will be very nice.

"When I got the award, I was very happy. I was proud. But I never tried to kill anybody. I tried to scare them and defend my life. God decides who is killed."

Paris Theodore is a weapons designer formerly employed by the U.S. Government on classified and covert weapons projects. He is pictured in his Manhattan office working on his self-designed "guttersnipe" pistol sight. In the background is a target for his QUELL system of combat

hand-gun shooting.

"Hollywood has been responsible for most errant ideas about combat and what actually happens in a shootout. Television and the movies mislead and misinform us regarding combat, and like so many six-year-olds sitting before our TV sets, (for that, indeed, is what we were), we absorbed that information like sponges.

"From the movies, we have learned to expect that when someone is shot in the arm, he reacts immediately by grabbing it with his free hand, wincing, and maybe uttering an "Unh!" When he is shot in the chest, a spot of blood appears and he is thrown backward, usually with arms flailing, to land motionless and silent.

"The truth of the matter is that no bullet from a sidearm, no matter what the caliber, will bowl a man over. The "stopping power" or striking force of the bullet can have no more impact than the recoil of the gun: otherwise' , the man pulling the trigger would be bowled over, because as every high school senior knows, every action is accompanied by a reaction of equal force in the opposite direction. The striking force of a modern .44 Magnum throwing a 240-grain ball at a muzzle velocity of 1,470 feet per second - almost twice that of a 19II .45 Colt semi-automatic would strike a stationary two-hundred-pound man at arm's length with one twentieth the force of another man walking into him.

"Also, one must remember that bullet wounds from a handgun are self-sealing and very rarely begin to show blood until moments after the crucial confrontation. And with very few exceptions, a bullet entering the body causes no immediate pain and cannot be felt entering.

"A member of the old NYPD Stakeout Unit once told us, ‘If they hit the ground with their legs crossed, they're dead. No further shooting of that felon is required. Go on to the next one.’ As fate would have it, this has proven to be an excellent rule-of-thumb.

"One must never make the mistake of taking a cue from either the opponent's facial expressions or words – which historically have been used deceptively -- and one cannot believe in ‘knock-down power.’ The closest thing to it in combat is a ‘cadaver reaction’ or a nervous spasm, both of which happen when the brain fires a confused barrage of synapses simultaneously when the opponent is shot (or possibly even when he thinks he is about to be shot). That can make a person scream, twitch, jump, or defecate, but it has no bearing on the number of foot-pounds of energy just delivered by a bullet.

"I conceived of the QUELL system of combat handgun shooting to address these realities."

George W. Gardner Chronology

1940 Born July 22 in Albany, New York.

1959 Spends gap year after graduation from high school trapping in the Adirondacks.

1960 Enrolls at University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

1961 Travels to Japan for first time.

1962 Hitchhikes to Mexico for the first time. Wins National Collegiate Photography Contest.

1963 Photographs Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington, August 28th.

1964 Graduates University of Missouri with a B.A. in Anthropology

1965 Photographs Ku Klux Klan rally in Southern Maryland.

1966 Photographs Blake Hobbs, the "Music Man of Harlem."

1967 Photographs in Hough neighborhood in Cleveland Ohio, a year

after the riots of July 18-24, 1966. Documents Latino immigrant community and Senate sub-committee meetings on migrant labor in Rio Grande City, Texas.

1968 Art Institute of Chicago purchases 10 of his prints.

1969 Photographs in the aftermath of racial violence perpetrated on the Black community of Cairo, Illinois.

1969 Included in The Museum of Modern Art, New York exhibition “Contemporary Photography II.”

1970 Makes his first of several annual trips to New Orleans to photograph Mardi Gras in the company of photographer Charles Gatewood.

1972 Photographs the Democratic National Convention in Miami, Florida. Makes his first aerial photographs.

1976 Fat Tuesday, a limited-edition portfolio of photographs by George Gardner and Charles Gatewood, published.

1982 America Illustrated: Photographs by George W. Gardner, 1960-1980, published.

1985 Gun People published.

Sampling of areas photographed by George by year:

1960 Columbia, Neosho, Aurora, Rocheport, and Poplar Bluff, MO; Seattle, WA; Nebraska

1961 Osaka, Tokyo, and Hokkaido, Japan; Columbia, MO; Pittsburgh, PA; Utah

1962 St. Louis, Columbia, and Girardeau, MO; Chicago, IL

1963 Columbia, MO; Washington, D.C.; Mexico

1964 Columbia, MO; New York City, NY

1965 San Antonio, TX; New York City, NY; Delaware/Southern Maryland; Danbury, VA; Buck County, PA; Cherry Valley, NY; Trenton, NJ

1966 Ava and Boone County, MO; West Texas; Adirondack Mountains and Lake Placid, NY; Mansfield, MO; Black Rock, NY; Rocky Mountain National Park, CO

1967: Cleveland, OH; St. Louis, Aurora, Washington and Columbia, MO; Rio Grande City and Brownsville, TX; Appalachian Mountains and Welch, WV; Wilmington, DE; Harlem, NY; Iowa; Blair, NE; Oklahoma; Arizona; California; Las Vegas, NV; Detroit, MI; Mexico

1968 West Harlem, NY; Washington, D.C.; Atlanta, GA; Atlantic City, Union City, New Brunswick and Camden, NJ; Blair, NE; Langhorne, PA; Jefferson County, NY; Welch, WV; New York City, NY; Lynchburg and Fall Creek, VA; Decorah, IA; Cherokee, TN; San Antonio and Waco, TX; St. Joseph and Columbia, MO; Baltimore, MD; Indiana; Mexico

1969 St. Louis and Marshall, MO; Cairo, IL; Washington, D.C.; Wilmington, DE; Colorado; Detroit, MI; Gary, IN; St. Paul, MN; New Haven, CT; Atlanta, GA; Penobscot-Old Town, ME; Santa Fe and San Rafael, NM; New York City and Adirondack Mountains, NY; Hay, KS; Green River, WY; Santa Monica and Los Angeles, CA; Las Vegas, NV; Miami Beach, FL; Arizona; New Hampshire

1970 Death Valley, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Big Sur, Salinas, Carmel/Monterey, Pt. Lobos, Santa Barbara and Sierra Nevada Mountains, CA; Gallup, NM; Denver, CO; New Orleans, LA; Cairo, IL; Hilton Head, SC; New York City, Staten Island, Chatham and Long Island, NY; Cambridge and Boston, MA; Philadelphia, PA; Washington, DC; North Carolina; Knoxville, TN; Blair, NE; Grand Canyon, AZ; St. Louis, MO; Miami, FL

1971 Decorah, IA; New York City, Coney Island and Hillsdale, NY; Blair, NE; New Orleans, LA; Connecticut; Reston, VA; Mississippi; Washington, DC;

1972 New York City and Hudson, NY; Blair, NE; Waterloo and Decorah, IA; Miami, FL; New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Metairie, LA; Wiscasset, ME; Dallas and Arlington, TX; St. Louis, MO; Washington, DC; Cairo, IL; Paterson, NJ; Hawaii; San Francisco, CA; Farmington and Gallup, NM; Arizona; Cincinnati, OH; Elko and Lake Tahoe, NV; Kansas; Gatlinburg, TN

1973 Washington, DC; New Orleans, LA; New York City, Hudson and Watkins Glen, NY; Fort Dix, NJ; New Brunswick, Canada; Nashville, TN; Bismarck, ND; Parkville, MO

1974 Newark, NJ; Toronto, Canada; Chicago, IL; New York City and Westchester County, NY; Michigan City, IN; New Orleans, LA; Lexington, VA; New Haven, CT; Cincinnati, OH; Brinkley, AR; Haiti

1975 Washington, DC; Chicago, IL; Cincinnati and Cleveland, OH; New York City and Hillsdale, NY; Blair, NE; Current River, AR

1976 Detroit, MI; New York City, Flushing, Dover Plains and Hudson, NY; Georgia; Marlboro and Amherst, MA; Saco and Owls Head, ME; Madison, WI; Iowa; Boone County and Hannibal, MO; Illinois; Denver, CO; New Orleans, LA; Death Valley, CA; Bowling Green, OH

1977 New York City and Coney Island, NY; Boston, MA; Clinch River, TN; Miami Beach and Daytona, FL; Okefenokee Swamp, GA/FL; New Orleans, LA; Oshkosh, WI; Bowling Green, OH; Detroit, MI; Seaside Park, Wildwood and Atlantic City, NJ; New Hampshire; Chicago, IL

1978 Four Corners region, Gallup and White Sands, NM; Hilton Head, SC; Colorado; New York City, Hillsdale and Cooperstown, NY; Washington DC; Akron, OH; Boston, MA; Rhode Island; Los Angeles, Siskiyou County and San Francisco, CA; Portland and Salem, OR; Hoover Dam, NV; Chicago, IL; Lake Powell and Page, AZ; Blair, NE; Blythe, CA

1979 Durham, NC; Philadelphia, PA; Washington, DC; Chicago, IL; Calhoun, GA; New Orleans, LA; Santa Barbara, CA; Arlington, TX; New York City, NY

1980 Chicago, IL; New York City, NY; Minneapolis, MN; Miami, FL

1981 Blair, NE; New Orleans, LA; Bisbee, AZ; Merida, Mexico

1982 Santa Paula Valley, CA; New Orleans, LA; Knoxville, TN; Carnation Gulf, Northwest Territory, Canada; Dayton, OH

1983 New Orleans, LA; New York City and Columbia County, NY

1985 Croton-on-Hudson, NY; Baltimore and Chestertown, MD

1986 Chatham, NY; Great Barrington, MA

1987 Blair, NE

1988 Columbia County, Philmont, Taghkanic, Craryville, Austerlitz and Kinderhook, NY

One-person Exhibitions

2010 KMR Arts, Washington Depot, CT

2010 Deborah Bell Photographs, New York, NY

1983 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA

1982 Douglas Kenyon Gallery, Chicago, IL

1980 Catskill Center for Photography, Woodstock, NY

1979 Midtown Y Gallery, New York, NY

1978 Sunprint Gallery, Madison, WI

1978 Midtown Y Gallery, New York, NY

1967 Purdue University, Lafayette, IN

Group Exhibitions

2012 L. Parker Stephenson Gallery, New York, NY, “A Tad Bit Strange and Somewhat Surreal: Photographs from the '60s and '70s”

1981 Colgate University, Hamilton, NY and traveling, "22 Photographers: Work by the Recipients of the 1980-81 CAPS Fellowship Awards"

1979 The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, “Discovering America: A Tribute to Hugh Edwards”

1977 Neikrug Gallery, New York, NY, “Rated X”

1969 The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, “Contemporary Photography II”

Publications

2011 B&W+Color, Issue 87, December. Profile: George Gardner

1985 Gun People, Dolphin Book, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY

1983 George W. Gardner, 1960-1980, The Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA

1983 Documentary Photography, Time-Life, Inc., New York, NY [revised edition]

1983 Twixt: Teens Yesterday and Today, Franklin Watts, New York, Sydney & Toronto, 1983, p. 43 [top left] & p. 83 [top left]

1982 America Illustrated: Photographs by George Gardner, 1960-1980, Tackfield Ltd., London & Chicago, IL

1980 Popular Photography Annual

1978-1994 Classic Country Inns of America Series, 1978-1994

1977 Popular Photography “How-To Guide,” pp. 22-34, pp. 86-91 & pp. 114-116

1976 Fat Tuesday, limited edition portfolio of twenty photographs by George W. Gardner and Charles Gatewood

1975 Camera 35, July 1975, pp. 53-57

1972 Creative Camera, February 1972 [text, photographs, & cover photograph]

1972 Camera 35, March 1972, pp. 38-47

1972 Camera 35, October 1972, pp. 22 & 32 [essay]

1966 Trans-action, December 1966

1965 Infinity/American Society of Magazine Photographers, Vol. 14, no. 6, June 1965, pp. 16-21

1962 Alumnus/University of Missouri Magazine, September 1962

Collections

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

DePaul University Art Museum, Chicago, IL

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College, Chicago, IL

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

International Center for Photography, New York, NY

Awards

1980-1981 New York State Creative Artists Public Service (CAPS) Fellowship

MORE ABOUT GEORGE GARDNER

After graduating from high school Gardner took up photography as a means to record a winter spent as a trapper in the Adirondacks wilderness. Upon entering the University of Missouri in 1960, he began to photograph for the school’s yearbook and alumni magazine.

As a student, he won the National Collegiate Photography Competition sponsored by Kappa Alpha Mu (KAM) in two consecutive years, 1962 and 1963. Kappa Alpha Mu was the national photojournalism student affiliate organization of the National Press Photographers. The award was a week in New York shadowing the Life magazine photography staff.

In the American Alumni Council Magazine Competition two of his photographs were selected among the 23 best photographs to appear in alumni magazines in the U.S. and Canada. They were exhibited at the American Alumni Council conference.

In 1972 Camera 35 published an essay by Gardner on the Black United Front, a militant group in Cairo, Illinois, with photographs from the pivotal year of 1970. Trans-action, a social science journal, published his photographs on the aftermath of racial unrest in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1966, which was triggered by poor housing, police harassment, and commercial exploitation by local merchants in the city’s African-American Hough neighborhood.

Beginning in about 1970 and for several years thereafter, he covered the annual Mardi Gras festival in New Orleans in collaboration with Charles Gatewood, legendary photographer of the erotic, whom Gardner befriended in college. Their joint Mardi Gras pictures were published as Fat Tuesday, a limited-edition portfolio of twenty photographs, and appeared in Camera 35 and Rolling Stone magazines.

His stock photographs have been published in Harper's, The New York Times, Life, and textbooks from Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Random House, Houghton Mifflin and others.

All photographs © 2021 George W. Gardner

Text © 2021 Andrew Smith Gallery

Text © 1985 Patrick Carr

(505)984-1234

Hours: Monday – Saturday 10-4

Andrew Smith Gallery Arizona LLC

Private viewing rooms, print receiving and cataloguing office:

330 E Convent Ave., Tucson, AZ 85701

Business office for invoice, billing, and payments:

10900 E. Roger Rd., Tucson, AZ 85749